The confidence fairy refers to the criticism that cutting government spending will lead to renewed confidence and economic recovery.

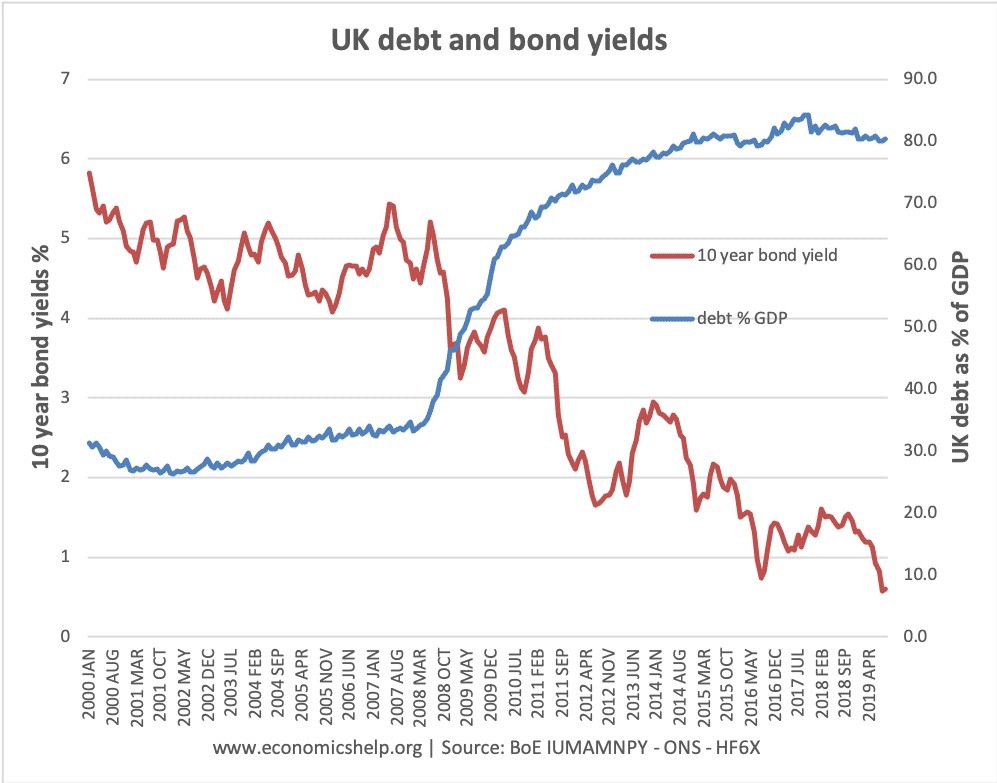

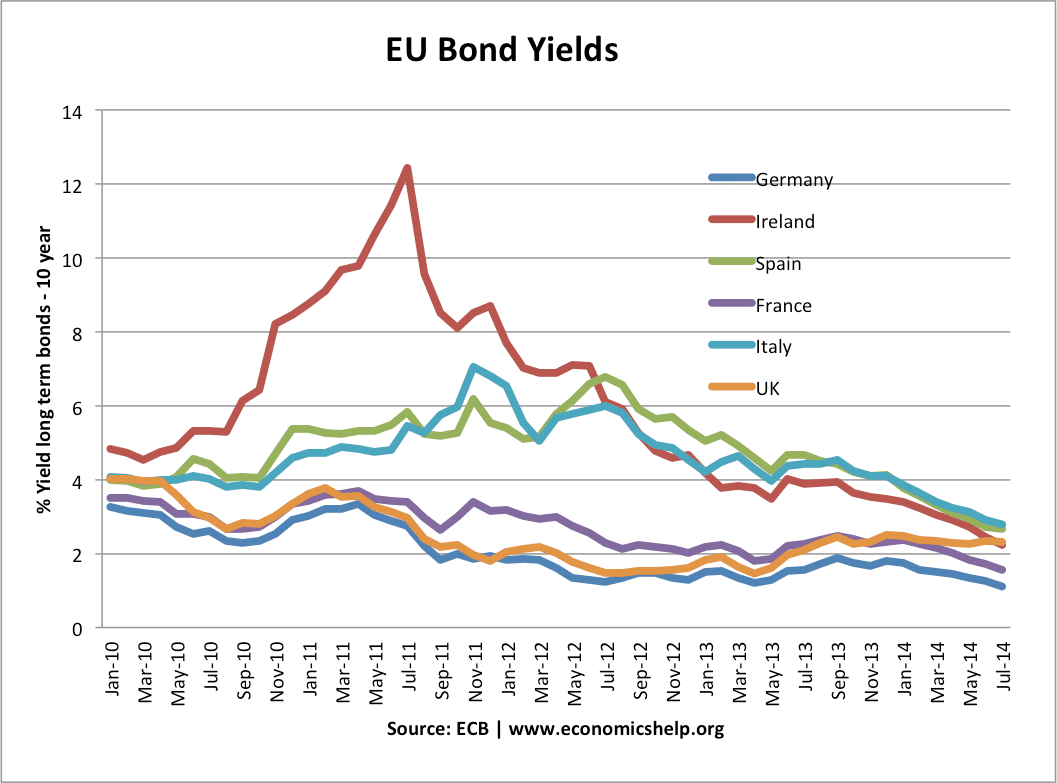

In response to the economic crisis of 2008, many economies faced large budget deficits – due to cyclical factors (e.g. falling tax revenue in recession) and also underlying structural deficits (e.g. growing welfare bills). Some countries in the Eurozone also experienced rapidly rising bond yields as markets feared there was risk of default.

Therefore, many economists suggested it was necessary for the government to cut spending and target deficit reduction. The argument was that cutting government spending would reassure markets because it shows governments have a clear strategy for reducing debt levels and avoiding default. With a rapid cut in government spending and deficit reduction, it should help bond yields remain low. These low interest rates and strong action would encourage business to invest. Therefore, the private sector should take over the role of the public sector.

For example, in 2010, Jean-Claude Trichet of the ECB stated that austerity could inspire confidence.

“The idea that austerity measures could trigger stagnation is incorrect,… confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery.” – J.C. Trichet (double dip recession)

However, critics (notably Paul Krugman) argue that cutting spending in a recession does not improve consumer or business confidence. In fact, it can actually make things worse. Cutting government spending leads to a further fall in demand, lower growth, higher unemployment and actually a decline in confidence. In 2010, Mr Blanchard, chief economist of the IMF, stated that authorities should not rule out another fiscal boost, despite debt worries. He claimed:

“If fiscal stimulus helps avoid structural unemployment, it may actually pay for itself,” (1)

Furthermore, in a serious balance sheet recession and liquidity trap, some economists argue there is little risk of rising bond yields in the short term. (The Eurozone has separate issues because no lender of last resort)

This is because in a liquidity trap, there is a rise in private sector saving and strong demand for government bonds. The Keynesian approach is, therefore, to increase government spending to offset the rise in private sector saving. This enables economic recovery and an improved cyclical deficit. When the economy has recovered and is showing signs of private sector growth, only then should the government should tackle its budget deficit.

Confidence Fairy in UK

In June and October, 2010, the chancellor announced spending cuts of up to £81bn over the next 4 years. In particular, this raised prospect of public sector job cuts.

“Up to 500,000 public sector jobs could go by 2014-15 as a result of the cuts programme, according to the Office for Budgetary Responsibility.” (Spending Review 2)

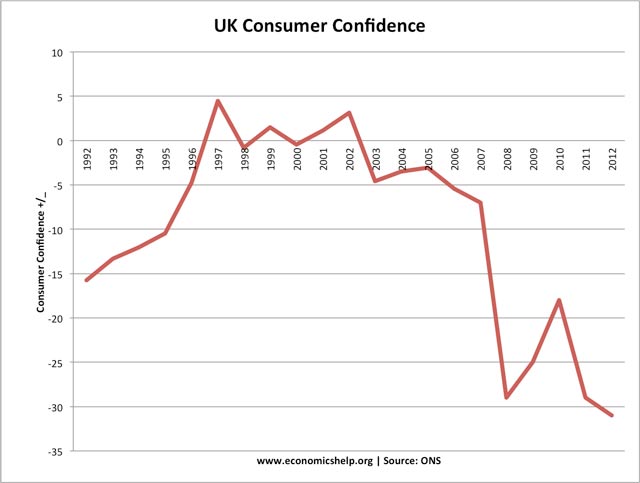

What Happened to Consumer Confidence in the UK?

After recovering from the worst of 2008, consumer confidence fell to a record low by the start of 2012.

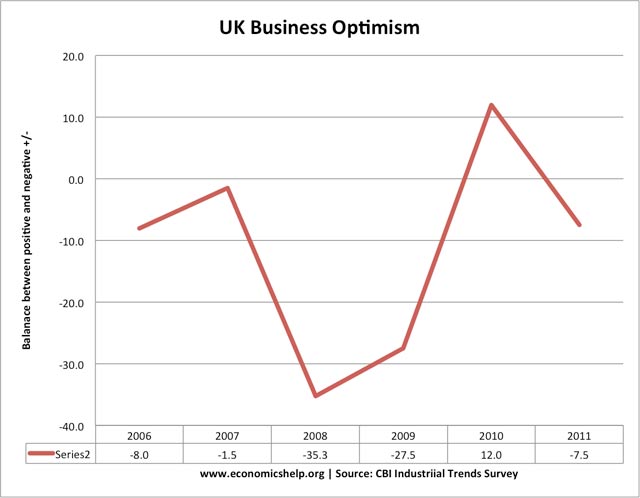

UK business confidence also fell from +12 in 2010, to -7.5 in 2011. Though it was more resilient than consumer spending.

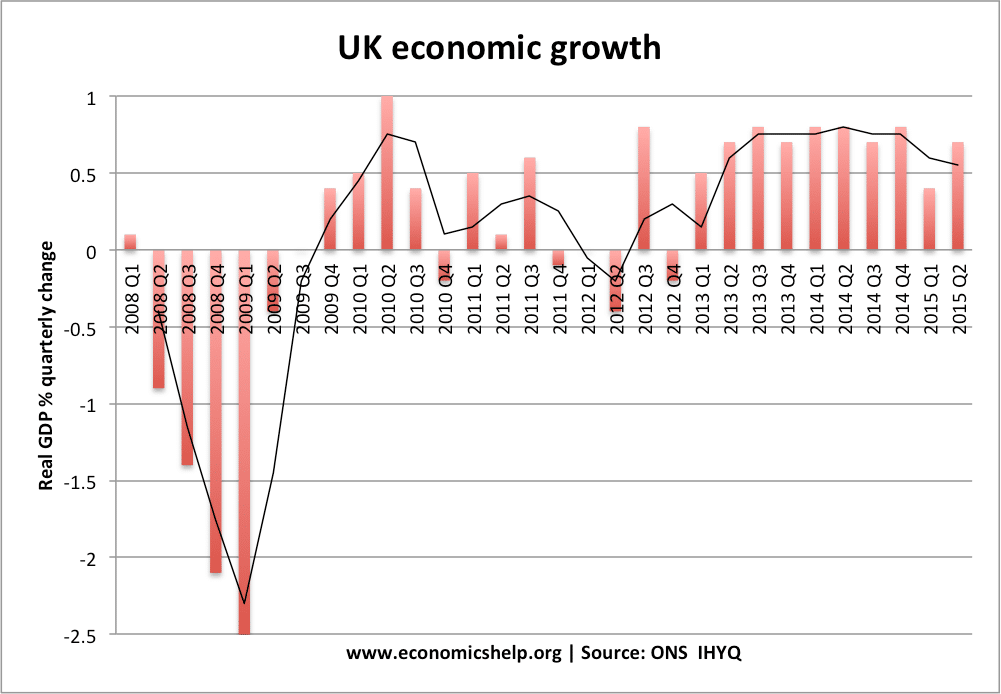

What Happened to Economic Growth?

After a brief recovery 2009 Q3 to 2010 Q3. The spending review coincided with an end to the recovery and subsequent double-dip recession at the start of 2012.

In other countries, Ireland, Greece and Spain, have also pursued austerity policies. This has led to similar falls in economic output, and has also failed to reassure bond markets. Despite spending cuts, bond yields have continued to rise because of fears over long term growth prospects in Eurozone.

Related

Tejvan,

We know that any decrease in demand has cumulative effects. Sure.

We also know that the reason for the critique of government spending is a product of citizen reaction to the misallocation of capital (taxes), and that they are seizing an opportunity to reduce this misallocation when it occurs.

Karl smith argues we ought to reduce taxes and increase borrowing during these periods. And while Karl argues that it’s just cheap, I argue that while it’s cheap, it assuages the conflict that naturally arises due to the public perception of unfairness by privileged government employees with privileged schedules and privileged retirement packages and the privileged insulation from the market.

Some of us (the ‘hard right’ like me, and the progressive left like Galbraith) recommended that we directly pay down mortgages during the crisis as well.

Both of these solutions would have had more positive effects than rescuing the banking system. The most important effect, from an Austrian’s viewpoint, is that they would have limited the worldwide recalculation of prices caused by the rapid decline in assets. Instead of bailing out consumers we bailed out investors.

People don’t like anything unfair. The notion of a collective good cannot ignore sectoral injustice.