Readers Question. Can you explain why the Government and Economic Commentators are talking about a multiplier (in relation to budget cuts) of between 0.5 and 1, whereas I always thought that the GDP multiplier was bigger than this.

Just to summarise a multiplier of 0.5 would mean fiscal consolidation (spending cuts) of £1bn, would lead to a drop in GDP of only £0.5bn. In other words, they hoped fiscal consolidation would be successful and only have a limited impact on reducing economic growth rates.

However, evidence from the IMF and other studies have shown the fiscal multiplier has proved much higher. In fact a multiplier of up to 2. (for every spending cut of £1bn, we have seen GDP fall £2bn. See: Fiscal multiplier and European austerity).

Essentially, this shows the limitations of using economic models which are applied during very different economic circumstances. If you look at previous attempts at fiscal consolidation undertaken during strong economic growth (e.g. Canada in 1990s), a multiplier of 0.5 would be quite reasonable.

However, there was an unwillingness to admit that the economic situation in the aftermath of a financial crisis and liquidity trap was very different.

Why might the Government and European Commentators expect a multiplier of 0.5?

To some extent, I answered this yesterday on the post – why austerity will increase the budget deficit. But, just to recap, the may have hoped for a multiplier of 0.5 because:

1. Expansionary monetary policy. With spending cuts, usually a Central Bank can cut interest rates and loosen monetary policy so that there is a boost to demand to offset the impact of tax increases and spending cuts.

- But, the EU and UK government should have realised that interest rates were already at record lows in 2010. Quantitative easing has done little to boost spending in the UK. In Europe, the ECB has never showed any real sign of loosening monetary policy in response to fiscal consolidation. In fact in 2011, the ECB increased interest rates over misplaced fears on inflation.

2. Private Sector Crowding in. If the economy is at full employment, a cut in government spending and lower borrowing will tend to cause private sector crowding in. This means that as government spending falls, there is scope for the private sector to spend more. Thus deficit reduction causes a change in the sector of the economy, but not a fall in demand. This occurs because rather than buy government bonds, the private sector will now have more funds to invest in private sector investment.

- The problem is that the recession is so steep that the private sector are reluctant to invest in private sector spending. Also, even if they do want to invest, banks are unable / unwilling to lend to the private sector. Therefore, cut backs in government spending haven’t been offset by growth in the private sector. There has been no ‘crowding in’ of private sector.

3. External Demand. Fiscal consolidation can often be offset by a devaluation and growth in external demand (exports).

- However, this is a European wide recession, and European wide fiscal consolidation. Who is going to export to who? Even though the UK saw a depreciation in the exchange rate during 2009, there was little export led growth to a recession hit Eurozone.

4. Confidence. There was a very strong belief amongst the UK and EU, that austerity would improve confidence.

As Jean Claude Trichet stated in 2010.

Everything that helps to increase the confidence of households, firms and investors in the sustainability of public finances is good for the consolidation of growth and job creation. I firmly believe that in the current circumstances confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery, because confidence is the key factor today.

The argument is that if private sector is concerned about the size of government borrowing and rising bond yields, then they will hold back from investment. However, if the government pursue ‘credible’ deficit reduction policies, this will give business and consumers more confidence to spend and invest.

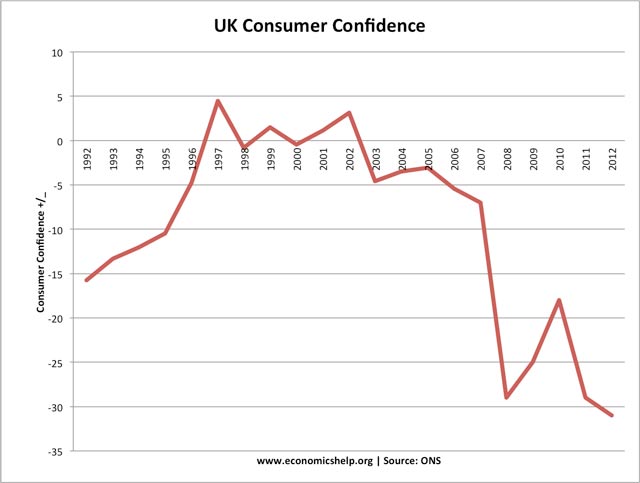

Notice: double dip fall in consumer confidence after austerity measures announced in 2010.

The problem is that this didn’t occur. In fact austerity measures severely hampered levels of consumer confidence. (see: UK consumer confidence). Public sector job losses and fears over future austerity led to lower spending. Austerity has not inspired confidence across Europe. This was at best overly optimistic, at worst it was a serious misunderstanding of the nature of consumer and business confidence. It also reflects a misplaced obsession with government deficits as the primary economic objective. Do people really rejoice and go out and spend, if the government cut back the number of civil servants.

Other Factors Why they Hoped for a low Multiplier

- Fears over the bond market. The Eurozone has rapid increases in bond yields and this was seen as a sign to pursue austerity (even though rising bond yields are as much due to forecasts of low growth and falling GDP)

- In the UK, the government took fright at rising bond yields in the Eurozone – even though there was no reason to believe this would happen to a country with its own currency.

- The strange political attraction of austerity. In the aftermath of a the financial crisis, it sounds good to talk tough on debt, moral responsibility e.t.c. It’s not always easy to sell Keynesian economics to a public who think borrowing must always be bad.

- Opportunity to reform welfare. Some may argue the government are quite happy for a debt crisis to give an excuse to tackle long-term reform on welfare payments.

Related

One could argue that Keynesian stimulus was alaredy discredited from 1930 1940, when FDR tried to spend his way out of the GD with public works projects. It is widely acknowledged that it was the massive investment in the WWII war machine that finally pulled the economy back to growth. This deficit spending was done for investment in productive machinery, not entitlements, and was financed largely by our own citizenry rather than foreign powers.

The moderate public work projects of FDR in the 1930s, were quite relatively successful. The US economy did show reasonable signs of recovery. One of the tragedies of the 1930s was the reversal of fiscal expansion in the 1937 – when worried about size of deficit, the US reversed fiscal and monetary policy – causing a second recession of 1937. An unnecessary double dip recession, that wouldn’t have occured if they had pursued different policies.