Quantitative easing is an unorthodox monetary policy aimed at stimulating economic growth and preventing a fall in the money supply. Just to recap, Q.E. involves:

- Central Bank creating money electronically.

- Using this extra money to purchase government bonds (and other securities) from banks and financial institutions.

Q.E aims to:

- Increase bank liquidity. When commercial banks sell bonds to the Central Bank, they have an increase in their cash reserves. This increase in cash deposits should, in theory, encourage commercial banks to lend to businesses.

- Reduce interest rates. Through buying government bonds, the market price of bonds rises, leading to a reduction in long-term interest rates. Lower interest rates should, in theory, encourage greater economic activity in the economy.

What happens when quantitative easing ends?

There will come the point when increased economic activity means the Central Bank no longer feels the need to buy more securities. At this stage, the increased money supply from quantitative easing may be inflationary because, with increased confidence, the banks now start to lend the cash that they have previously been hoarding (saving). (though there is no sign of this occurring yet)

Reversing Quantitative Easing

At some point, the Bank of England will reverse the policy of quantitative easing. This involves selling the government bonds it holds on the open market. This will cause:

- A fall in the price of bonds, due to increased supply on the market.

- As bond prices fall, the bond yield will increase. Therefore, we will see rising interest rates.

- A decrease in cash reserves in banks. If banks buy government bonds, they will have a fall in their cash reserves; this could lead to a fall in the money supply, lower growth and possibly even deflation.

So will we get inflation or deflation when quantitative easing ends?

We don’t really know.

- If the Central Bank extends too much extra money and allows this extra money to stay in the economy during a strong recovery, then it is likely to contribute to inflation.

- If the Central Bank reverse quantitative easing too early – if they reverse quantitative easing when the economy is still in a liquidity trap / stagnant growth, then it could cause the economy to stagnate further. If quantitative easing is reversed when the economy is still weak, we could see deflationary pressures.

Therefore, the timing of quantitative easing becomes important. The hope is that the process of quantitative easing can be gradually reversed during a sustained economic recovery. Obviously, the Bank will not want 10-year. But, if it can sell £20bn every couple of months, the policy may be reversed without causing too much impact on the macroeconomy. If the economy is growing strongly, then the reduction in money supply and higher interest rates from Q.E, will be absorbed.

The other reason why it is hard to know what happens when quantitative easing ends is that it’s hard to know if quantitative easing has had much impact on stimulating the economy in the first place.

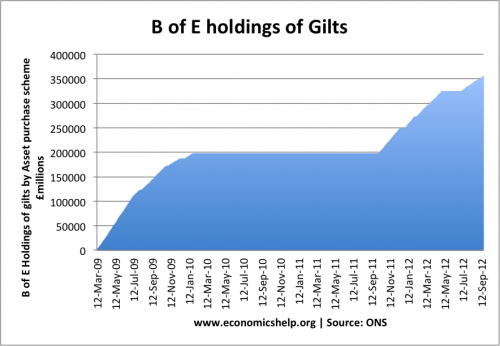

In the past few years, the Bank of England has increased its holding of government bonds (gilts) to over £350billion.

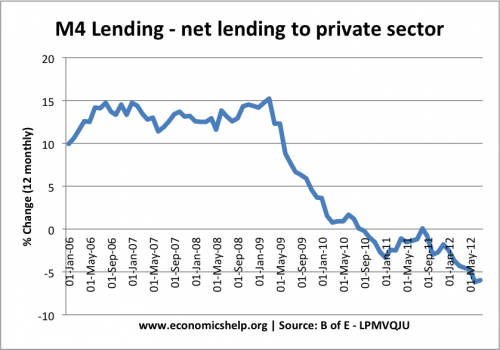

Yet, the impact on M4 lending has been limited. In 2012, we saw negative growth in M4 lending, despite the £350bn of extra securities.

This may look a failure – the broad money supply has still fallen, but, by comparison in Ireland during 2011 the broad money fell 28% (Money Week)

It is reasonable to surmise that the recession would have been deeper without this monetary stimulus of Q.E.

How will government borrowing be affected by the end of quantitative easing?

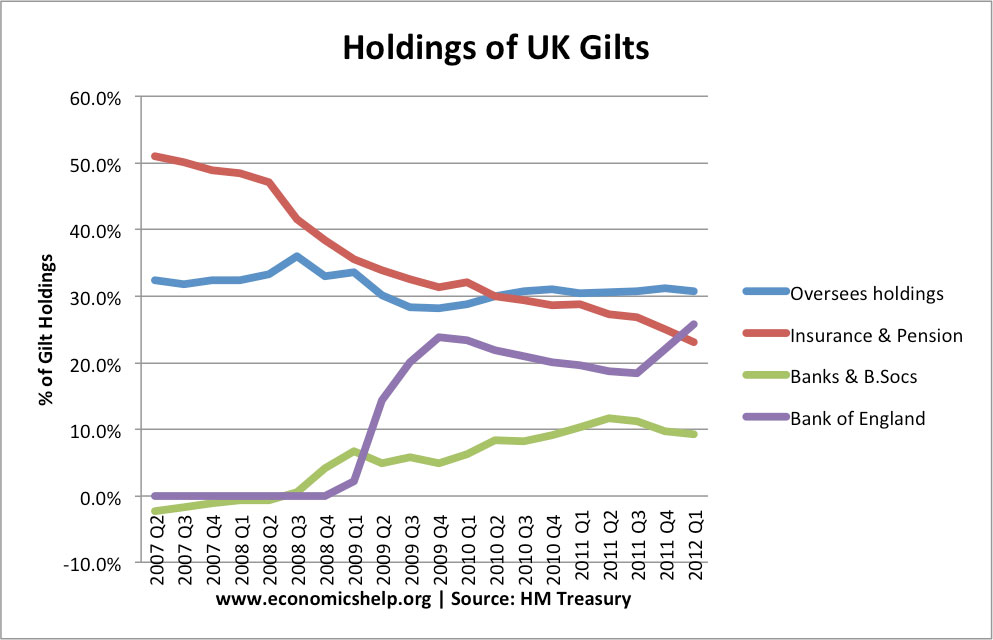

A rather ‘pleasant’ side effect of quantitative easing has been the fact that it has made it easier for the government to borrow. The Bank of England has become one of the principle buyers of government debt. (see: who owns government debt)

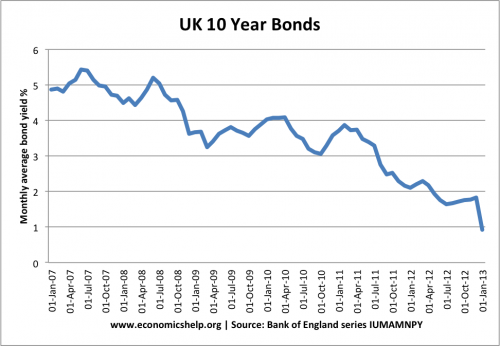

And despite record budget deficits, bond yields have fallen to record levels.

Recent UK Bond Yields

Source: Bank of England – 10 year bond yields

When quantitative easing ends, there will be no Central Bank to buy bonds. When quantitative easing is reversed, bonds will be sold onto the market. Some fear that this selling might cause the ‘bond bubble’ to burst. Bond prices will fall, and interest rates rise. This could make it very expensive for the government to finance it’s borrowing. Higher rates could derail the recovery.

With very low-interest rates, the annual debt interest payments are around £45bn, if interest rates rise significantly, this cost of interest payments will rise significantly. This will be an unwelcome consequence of reversing quantitative easing.

However, quantitative easing is not the only reason for low bond yields. Bond yields are low because in this liquidity trap, there is high demand for buying bonds. (see: reasons for falling bond yields)

Quantitative easing should only be reversed when the economy is growing strongly. When the economy is growing strongly, the government will see its debt burden fall. However, when the economy recovers and the Central Bank reverses Q.E. interest rates will definitely rise.

Conclusion

When Q.E. ends, we will see higher interest rates. But, hopefully, the end of Q.E means the economy is returning more to ‘normal’ levels of economic activity – growth of 2.5%, interest rates will rise back to more ‘normal’ levels. If nothing else, this return to ‘normality’ would be very welcome. However, there is no sign of this occurring in the foreseeable future.

It is hard to know exactly what will happen because there are few precedents for ending such a policy of quantitative easing.

Related

The trouble with QE as a booster to the economy is that it gives the money created to those who are saving, not spending. So they move their savings from one holding, Government bonds, into another, property, gold, more bonds, stocks and shares. But demand for real goods is not stimulated at all.

And now we have massive inflation…. geez, we should have read this closer 6 years ago….