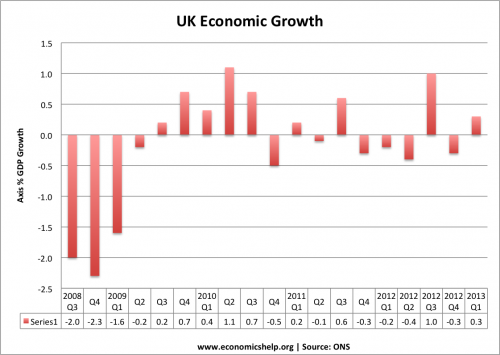

On the day Spain, announced its unemployment rate had increased to a truly staggering 27%, many see the UK’s anaemic growth rate of 0.3% in Q1 2013 as a ‘success’. But, it is worth noting UK real GDP is still considerably below its 2008 peak.

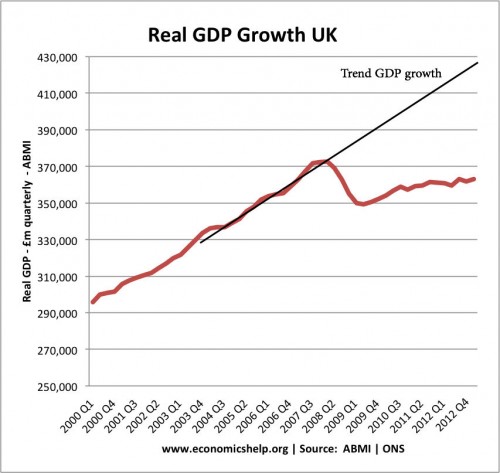

Dataset ABMI at ONS

When you look at GDP like this, the lost output and scale of the recession becomes more evident.

Using a very rough rule of thumb, if we had maintained the pre-crisis trend rate of economic growth, we might expect something like £425bn for Q1 2013, rather than the £361 bn. That’s very roughly £64bn less output than pre-trend growth. To get an annualised figure, GDP is roughly £248bn less than pre-trend output growth.

Given the loss of output, it raises the interesting question – how much structural deficit do we really have? Is the deficit not a consequence of this unprecedented economic stagnation?

Source: ONS

Given the scale of the credit crunch and global downturn, a deep recession was inevitable; in this climate to maintain pre-trend growth is unrealistic – but the recovery since 2010 has been very disappointing. It is an example of missed opportunities and a failure of political will to aim for full employment and economic growth; falling public sector investment came at the wrong time. Given the weakness of private sector spending, it is no surprise this created a large multiplier effect and a double dip recession.

If in 2010, a government had made its primary macro-economic objective as strong economic growth, we could have seen higher GDP, and ironically, they would be in a stronger position to reduce the budget deficit.

The fact we have avoided a triple dip recession, doesn’t change the fact that the current recession is longer lasting than the great depression and all subsequent UK recessions. See recessions compared. Usually, after a recession, you expect a bounce in growth as the economy makes use of spare capacity. The anaemic recovery suggests that the prolonged recession has led to a persistent loss of output and that means lost tax revenues and higher borrowing.

At least we are not Spain or Greece

If ever there was a question of damning with feint praise, we could claim justification that at least we are not Spain or Greece, who seem to be rushing headlong into an austerity induced depression of an unprecedented scale.

It is true that in comparison to several European countries, UK austerity is relatively mild. Spending cuts are relatively modest compared to other countries. However, it should be remembered in a recession with falling private spending, fiscal policy should be expansionary. Even mild spending cuts create strong downward pressures on demand. (see: do we really have austerity)

In the past few years, the UK has also experienced loose monetary policy, and a depreciation in the Pound. Both monetary policy and the exchange rate have been disappointing in boosting growth, but it is still better than nothing. The combination of low interest rates, a weak Pound, and a government muddling its way through fiscal policy will enable some recovery. But, if policy had been bolder – or even willing to adapt to changed facts, it could and should have been much stronger