Credit policy / financial policy is the use of the financial system to influence aggregate demand (AD). Monetary policy affects AD through the Central bank controlling interest rates and the money supply. Fiscal policy affects AD through the use of government spending and taxation.

Credit policy looks at factors such as:

- Bank lending rates to firms and households in the economy.

- The supply of credit and availability of loans from banks to firms and households.

In normal economic circumstances, it was felt the Central Bank could adequately control the economy through changing base rates.

When the Central Bank (e.g. ECB, Bank of England) changed interest rates, it had a strong influence on bank lending rates. When the ECB cut rates in 2001-03, bank lending rates fell, when the ECB raised rates in 2006-07, bank lending rates rose. Bank lending rates closely mirrored the Central Bank. Therefore, there was little attention paid to bank lending rates – there was no need.

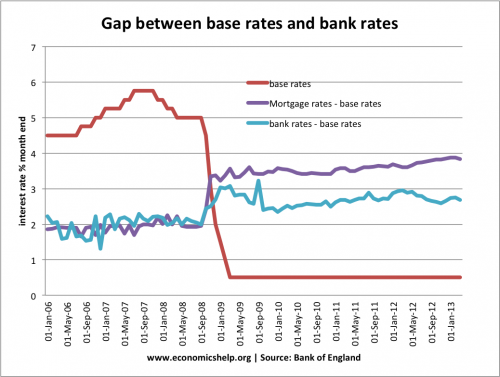

However, since the credit crunch, the normal relationship between Central bank base rates has broken down. In particular, when the main base interest rate was cut, firms – especially small and medium sized firms (SME) didn’t see the actual interest rate they paid cut.

See also bank and base rates in the UK

Implications of divergence between base rates and bank rates

This is very important for the effectiveness or not of monetary policy. Usually, if interest rates are cut from 5% to 0.5%, we would expect the loosening of monetary policy to boost lending, consumption and aggregate demand. But, that hasn’t been happening. Lending rates are still high, and credit tight. The base rate of 0.5% has become misleading to the actual reality of firms who face high borrowing costs.

Problems in the Eurozone

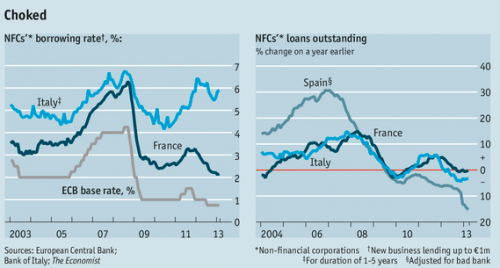

Source: Economists – Central bank has lost control over interest rates

This problem of bank lending rates is most noticeable in the peripheral Eurozone countries. Since the crisis, small and medium sized firms have actually seen an increase in borrowing costs. Bank rates have increased, making the 0.5% ECB rate meaningless. The Economist reports

‘SMEs in Spain and Italy must pay over 6% to borrow; money is tighter there than it was in 2005, even though the ECB’s rate is far lower.’ (Woes for small business in Europe)

The problem for SME (small and medium enterprise firms) is that they are too small to sell their own bonds. They are reliant on bank lending. But, because of the credit crunch and fears over bank stability, they are finding their borrowing costs increase.

The problem of bank lending rates

Eurozone countries like Italy and Spain are in recession. They are also trying to reduce budget deficits through government spending cuts and austerity. This contractionary fiscal policy in a recession is reducing aggregate demand. In this circumstance, you would want monetary policy to be expansionary – low interest rates and increased money supply. However, the low ECB interest rate is no longer affecting real financial variables. Firms in Italy and Spain are having to pay more on their debt interest payments. This leaves them less funds for investment. If firms did want to invest, they would face higher interest rates and tight supply.

These feeds a downward spiral. Because of austerity and high interest rates, consumers and firms are pessimistic about the state of the economy and so firms are reluctant to invest – even if they could afford it. The net result is that the high bank lending rates are discouraging investment and spending.

The problem of the Euro

The problem of high bank lending rates are greater in the Eurozone than the UK. This is because:

- Bond yields on Eurozone debt are higher, this puts an upward pressure on bank rates.

- Recession is deeper in the Eurozone because of the perceived need for greater austerity / problems of competitiveness.

- Concerns that the ECB will be slower more reluctant to bailout banks and act as lender of last resort. Though since 2012, the ECB has been more willing to intervene in bond markets.

- See also: problems of the Euro

Reducing Bank lending rates

In the current economic climate of Europe, reducing firms actual borrowing costs becomes an important priority. We could say this is the role of credit policy – reducing bank rates and increasing the supply of credit in the economy. How could the Central Bank / monetary authorities reduce actual bank lending costs?

- Funding for lending scheme. The Bank of England has tried to increase lending to small and medium sized firms by guaranteeing bank loans and allowing commercial banks to borrow at very low interest rates.

- The Central bank could buy SME loans from banks and non-banks to increase credit and reduce the cost of these loans.

- National lending bank. A third alternative is to set up a national bank specifically targeted at offering competitively priced loans to small firms.

- Guarantee Bank deposits to give greater confidence in the financial system. When the EU suggested Cyprus savers may lose their savings, this created financial instability and pushes up bank interest rates. Maintaining financial confidence is important for keeping low interest rates.

Combination of Fiscal, Monetary and Credit policy

It is worth bearing in mind that all policies are interrelated. Because Europe faces fiscal tightening and monetary tightening, it becomes important to consider credit policy and bank rates. The fact that bank lending rates have increased rather than fallen means that European economies face a triple downward pressure. In addition, you could add:

- Overvalued exchange rates in the Euro, leading to lower export demand

- European wide recession is holding back exports.

Conclusion

Credit policy has received perhaps less attention than it needs. The fact there is a greater divergence between bank rates and Central bank rates suggests that conventional monetary policy is inadequate for dealing with the consequence of a credit crunch and balance sheet recession. Policies to reduce bank lending rates have largely been untried, but if Europe is to avoid a prolonged depression it is something that needs close attention.

Related

- Third lever of macroeconomics at Economist.com

- Broken transmission at Economist.com

- Mend the money machine at Economist.com

I don’t agree when you say in respect of the Euro periphery that “In this circumstance, you would want monetary policy to be expansionary – low interest rates and increased money supply.”

The basic purpose of imposing deflation on the periphery is to get periphery costs down so as to enable them to regain competitiveness – though clearly there is a horrendous social cost to pay. But that’s common currencies for you.

Moreover, the periphery IS REGAINING competitivness. According to the second leader in the FT yesterday, Greece has regained two thirds of the competitiveness that it needs to regain.

So given the latter objective, it’s actually NOT DESIRABLE for “monetary policy to be expansionary” in the periphery.