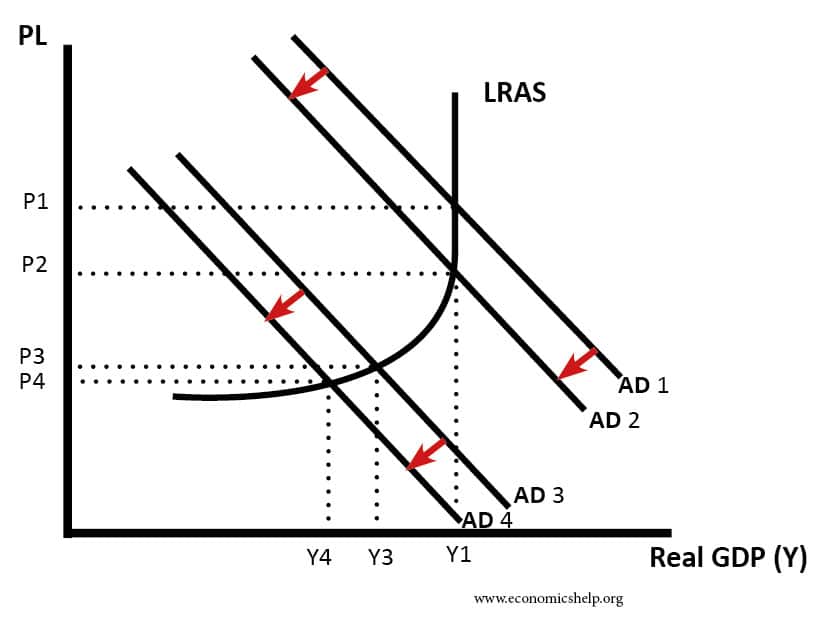

Credit policy / financial policy is the use of the financial system to influence aggregate demand (AD). Monetary policy affects AD through the Central bank controlling interest rates and the money supply. Fiscal policy affects AD through the use of government spending and taxation.

Credit policy looks at factors such as:

- Bank lending rates to firms and households in the economy.

- The supply of credit and availability of loans from banks to firms and households.

In normal economic circumstances, it was felt the Central Bank could adequately control the economy through changing base rates.

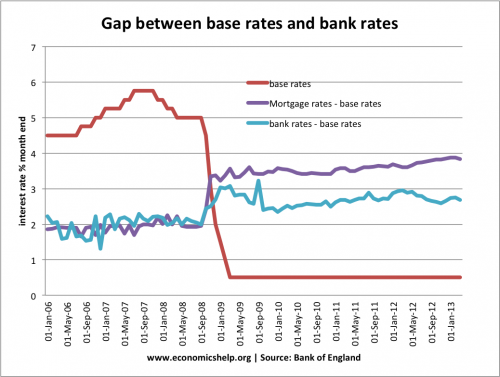

When the Central Bank (e.g. ECB, Bank of England) changed interest rates, it had a strong influence on bank lending rates. When the ECB cut rates in 2001-03, bank lending rates fell, when the ECB raised rates in 2006-07, bank lending rates rose. Bank lending rates closely mirrored the Central Bank. Therefore, there was little attention paid to bank lending rates – there was no need.

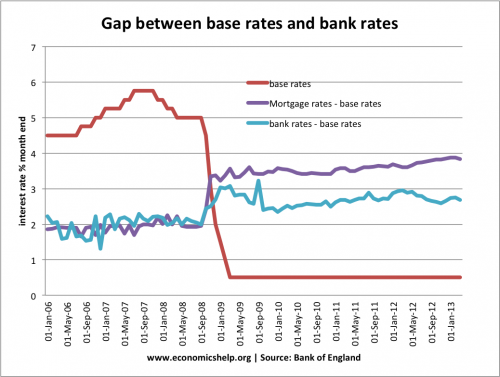

However, since the credit crunch, the normal relationship between Central bank base rates has broken down. In particular, when the main base interest rate was cut, firms – especially small and medium sized firms (SME) didn’t see the actual interest rate they paid cut.

See also bank and base rates in the UK

Implications of divergence between base rates and bank rates

This is very important for the effectiveness or not of monetary policy. Usually, if interest rates are cut from 5% to 0.5%, we would expect the loosening of monetary policy to boost lending, consumption and aggregate demand. But, that hasn’t been happening. Lending rates are still high, and credit tight. The base rate of 0.5% has become misleading to the actual reality of firms who face high borrowing costs.

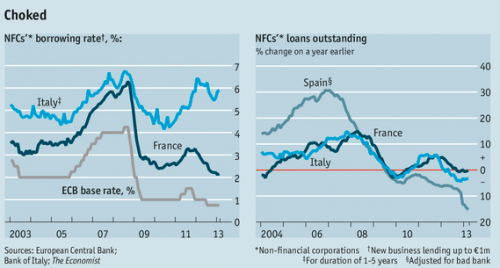

Problems in the Eurozone

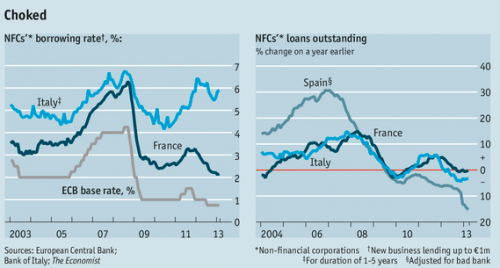

Source: Economists – Central bank has lost control over interest rates

This problem of bank lending rates is most noticeable in the peripheral Eurozone countries. Since the crisis, small and medium sized firms have actually seen an increase in borrowing costs. Bank rates have increased, making the 0.5% ECB rate meaningless. The Economist reports

‘SMEs in Spain and Italy must pay over 6% to borrow; money is tighter there than it was in 2005, even though the ECB’s rate is far lower.’ (Woes for small business in Europe)

The problem for SME (small and medium enterprise firms) is that they are too small to sell their own bonds. They are reliant on bank lending. But, because of the credit crunch and fears over bank stability, they are finding their borrowing costs increase.

Read more