Back in the summer of 2010, Apple launched the iPad. It was launched to great excitement and it seems the initial euphoria was well placed. From sales of zero at the start of 2010, the tablet market has expanded to over 100 million units a year as we come towards the end of 2013. Sales forecast predict global tablet sales will reach 200 million a year by 2016.

It is an astonishing growth and is changing the way people access information on the internet.

The decline of the traditional computer?

The rapid growth of tablets is bad news for sales of laptop computers and desktops. Laptop sales fell 8.6% in the Q3 2013, and sales of laptops have now fallen for six consecutive quarters; sales have fallen to levels last seen in 2008.

I often ask my students if they use tablets or computers, it is increasingly common for people to say they hardly turn on their computer, but just use tablet or mobile phone. On a personal note, I bought one of the first Ipads but I never really got on with a tablet (I sold it on ebay a few weeks later). Perhaps I am missing something? Though a mac-book air, is closer to a tablet than most laptops.

Apple Market Share of Tablets

Apple is the leading brand. Despite being the most expensive tablet, it still retains 45% of the market share. However, it has a serious competitor in the Android OS which is fairly close to Apple market share (though split amongst different manufacturers). Apple also has the advantage of being the most profitable, able to charge a higher price than many other tables. Apple benefits from:

- Being the first mover in the market.

- Apple compatibility with iPhone and other Apple products

- Strong brand loyalty

- Technological advances making it one of the best products.

Why is the price of tablets falling?

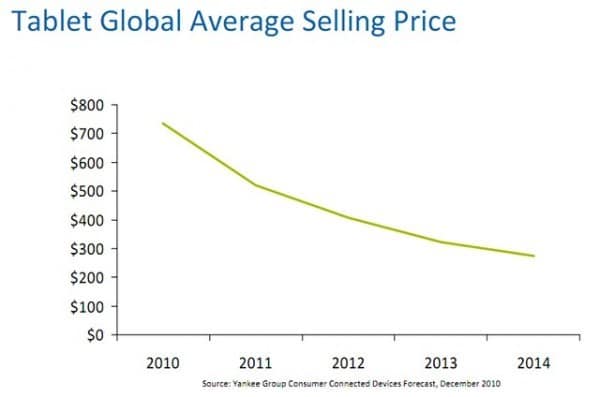

Since the introduction of the Apple iPad back in 2010 at a price of over $700, the average price of a tablet has been falling quite significantly, and market forecasts suggest it will keep falling. Note, this fall in price has occurred despite the rising demand. Several factors explain this fall in the price of tablets.

- Price skimming. When Apple launched the product at $700, there was an element of price skimming. Charging a high price to attract those customers willing to high price for a tablet. Since then, many new firms have been seeking to attract a new range of customers more sensitive to price. The price of an iPad could also be described as ‘premium pricing‘ – charging a high price to reinforce the impression Apple is the best quality. Recent tablet models are less keen to claim they are the best quality.