Politicians often promise tax cuts can lead to higher productivity, higher economic growth, and even pay for themselves through a boost to long-term incomes. These promises may chime with the electorate who tend to prefer promises of tax cuts. But, do tax cuts really increase economic growth?

There are two impacts of lower tax.

- Increasing demand in the short term

- The effect on supply and productivity in the long-term

Lower income tax rates increase the spending power of consumers and can increase aggregate demand, leading to higher economic growth (and possibly inflation).

On the supply side, income tax cuts may also increase incentives to work – leading to higher productivity.

However, the effect of tax cuts depends on how the tax cut is financed, the state of the economy and whether low tax rates actually increase productivity and the willingness to work.

The effects of reducing income tax rates

- Increased spending. Workers will see an increase in their discretionary income. With lower income tax rates, they would keep more of their gross income, so effectively they have more money to spend.

- Higher economic growth. With lower tax rates, we could expect to see a rise in consumer spending because workers are better off. Because consumers spending is a component of aggregate demand (AD) (roughly 60%), then a rise in consumer spending should cause a rise in AD, leading to higher economic growth.

- Government borrowing. Tax cuts will, ceteris paribus, lead to lower tax revenue and this is likely to cause higher borrowing. Though some economists believe income tax cuts can increase productivity, which offset this fall in revenue.

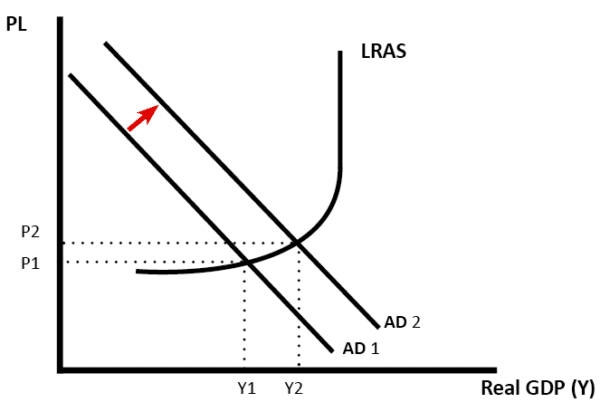

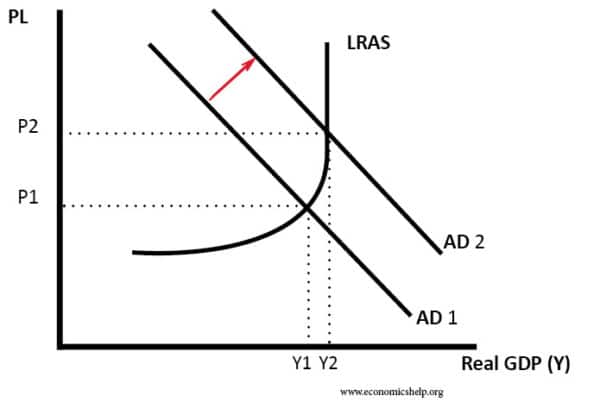

Effect of tax cut when the economy is below full capacity

Impact of tax cuts on AD/AS diagram, when there is spare capacity in the economy.

How are tax cuts financed?

Will a cut in tax really increase aggregate demand? Firstly, it depends on how the tax cut is financed.

- Tax cuts financed by spending cuts. Suppose the government offered £4 billion of income tax cuts, but at the same time cut £4 billion from welfare spending. In other words, the tax cut is financed by cuts in government spending. In this case, we will not see an increase in AD because some people are better off from the tax cut, but others will cut their spending due to lower welfare payments. There is no overall increase in injections into the circular flow of income. [In fact, those on welfare benefits are likely to have a higher marginal propensity to consume (mpc) than those on higher income levels so this could actually cause lower AD].

- Government borrowing. Alternatively, the government could finance the tax cut by increasing government borrowing. Would this increase AD?

- In a recession, we probably would see higher AD. This is because the government borrowing will be financed by people wanting to save anyway. In this case, the government is injecting unused resources into the circular flow. In a recession, the tax cut makes a big difference to people’s spending power

- If the government increases borrowing in a boom to finance a tax cut, we are more likely to get crowding out. This essentially means the government borrow more by selling bonds to the private sector. If the private sector buys government bonds, they have less money to invest elsewhere. Also, during high growth, higher borrowing may lead to higher bond yields, and these higher interest rates cause financial crowding out.

- Cutting taxes in a boom

Cutting taxes when the economy is already growing quickly is likely to cause inflationary pressures.

In 1988, chancellor Nigel Lawson cut income tax. The top rate of tax was cut from 60p to 40p and the basic rate from 27p to 25p. These tax cuts occurred during a period of strong economic growth; these tax cuts (combined with loose monetary policy) led to even higher economic growth, but inflation also increased to 8% in 1989 and caused a subsequent boom and bust. The tax cuts also caused a rise in import spending and an increase in the UK current account deficit.

- Tax cuts financed by improved productivity. If the economy sees rising productivity, then this can enable tax cuts. For example, if an economy saw productivity growth of 4% a year (e.g. due to new technology) then this high rate of economic growth would automatically lead to higher tax revenues (higher VAT, corporation tax). With this kind of economic growth, it may be possible to cut tax rates – but maintain tax revenue.

Impact of tax cuts on productivity

If we take a cut in income tax, it could also affect the supply side of the economy.

- Lower income tax rates may encourage people to work longer. Overtime is more worthwhile if you get to keep more of your income. Lower income tax rates may encourage people to move to that particular country. This is the substitution effect – work is more attractive with lower tax rates.

- However, there is also the income effect. With lower tax rates (and effectively higher wages), it is easier to get your target income by working fewer hours. Therefore, tax cuts may not increase labour supply because people don’t need to work more if work is more highly paid.

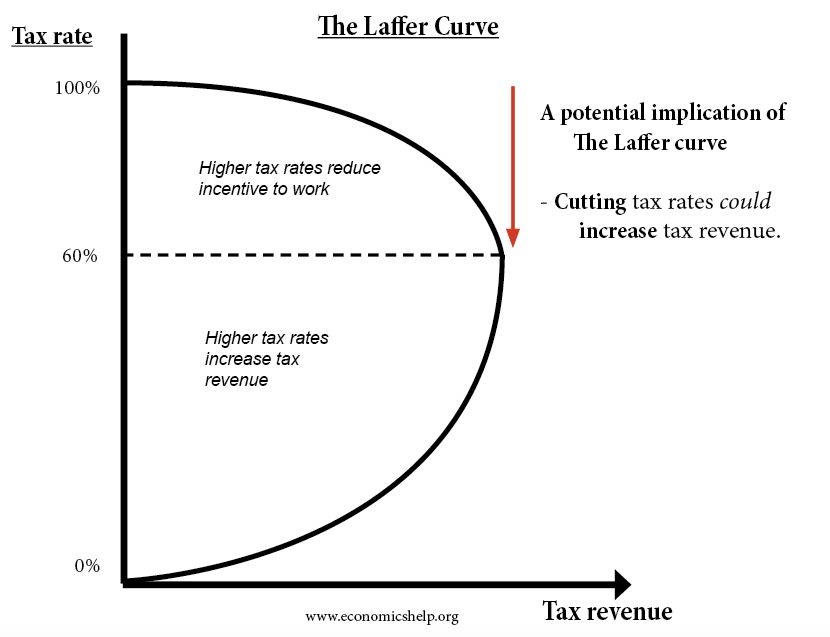

A controversial economic argument is the “Laffer Curve“. This argues that if you cut income tax rates, then the tax cut increases the incentive to work so much, that the government can actually gain more tax revenue. It seems to offer the best of both worlds – lower tax rates and higher tax revenues.

There is a debate about the extent to which tax cuts increase productivity and economic growth. If marginal income tax rates are very high, e.g. 80%, then cutting tax rates is likely to increase labour supply and productivity. But, with tax rates of 20 or 30%, cutting income tax rates is no guarantee of increasing productivity and growth.

Cut in indirect tax

If the government cut an indirect tax like VAT, the effect is similar. If goods are cheaper because of lower tax, consumers will effectively have more purchasing power. After buying the same number of goods, they will have more money left over. Therefore consumer spending may rise. There will be little impact on productivity.

Do tax cuts increase economic growth?

Short-term. If the economy is close to full employment with a low saving ratio, then tax cuts financed by borrowing from the private sector could well ‘crowd out‘ the extra disposable income consumers have. Therefore, the impact on growth is limited, but it will cause higher inflation.

However, in a recession, when saving rates are very high, then government borrowing doesn’t remove money from the economy because it was just been saved.

Ricardian Equivalence

Another issue is the idea that consumers may respond to tax cuts by deciding to save more. The reason is that rational consumers may see a tax cut financed by borrowing will lead to future tax rises. Therefore, consumers don’t spend the tax cut but save it for future tax rises. More on: Ricardian equivalence