Trickle down economics is a term used to describe the belief that if high-income earners gain an increase in salary, then everyone in the economy will benefit as their increased income and wealth filter through to all sections in society.

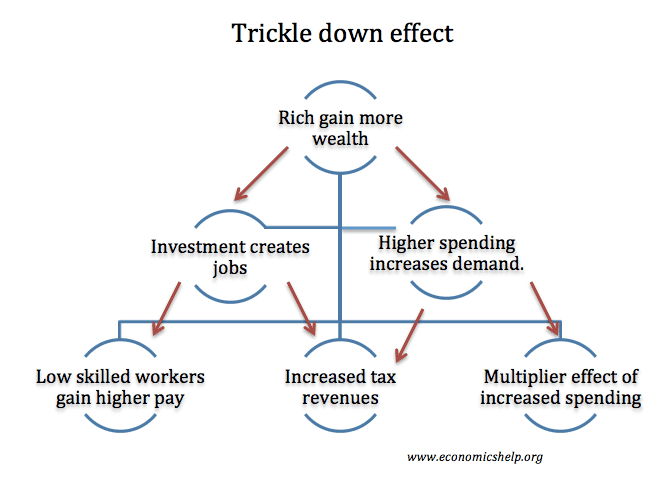

How the trickle-down effect may work in theory

If the richest gain an increase in wealth, then

- They will spend a proportion of this extra wealth.

- The extra wealth will cause an increased demand for goods and services, causing higher employment and a rise in wages.

- The higher wages will also cause a multiplier effect, e.g. if more chauffeurs are employed by the rich, the chauffeur will gain increased income and, in turn, they will increase spending in local businesses.

- A cut in taxes increases the incentive to work. Lower income tax encourages people to work longer. Lower corporation tax encourages business to invest, creating wealth.

- Alternatively, the wealthy may invest their increased wealth. If the wealth is invested in new businesses, it will create new jobs and increase the incomes of those employed.

- Higher spending and investment will stimulate economic activity leading to a rise in tax revenues (higher income tax, higher VAT).

- Higher tax revenues can fund public programmes such as healthcare, education and welfare payments to the poor.

Trickle-down effect and tax cuts

An important element of the trickle-down effect is with regard to income tax cuts for the top-income earners. It is argued that cutting income tax for the rich will not just benefit high-earners, but also everyone. The argument is as follows:

- If high-income earners see an increase in disposable income, they will increase their spending and this creates additional demand in the economy. This higher level of aggregate demand creates jobs and higher wages for all workers.

- Alternatively, increased profits for firms may be reinvested into expanding output. This again leads to higher growth, wages and incomes for all.

- Lower income taxes increase the incentive to for people to work leading to higher productivity and economic growth.

- The Laffer curve suggests cutting tax can even cause an increase in tax revenues as the lower tax rates are offset by higher growth.

A study by NBER June 1997 Engen and Skinner conclude that:

“cutting marginal tax rates across the board by 5 percentage points and cutting average tax rates by 2.5 percentage points would increase the growth rate of U.S. GDP by 0.3 percentage points per year.”

Video on Trickle-down economics

Criticisms of trickle-down economics

I have a joke about trickle-down economics. Only 99% of you will get it.

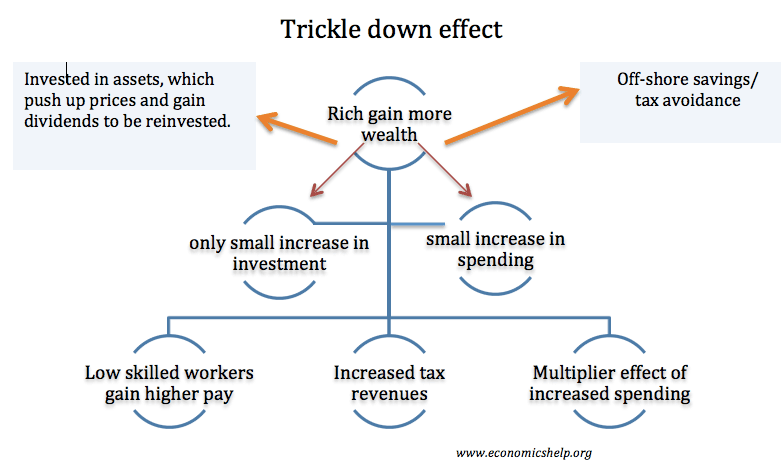

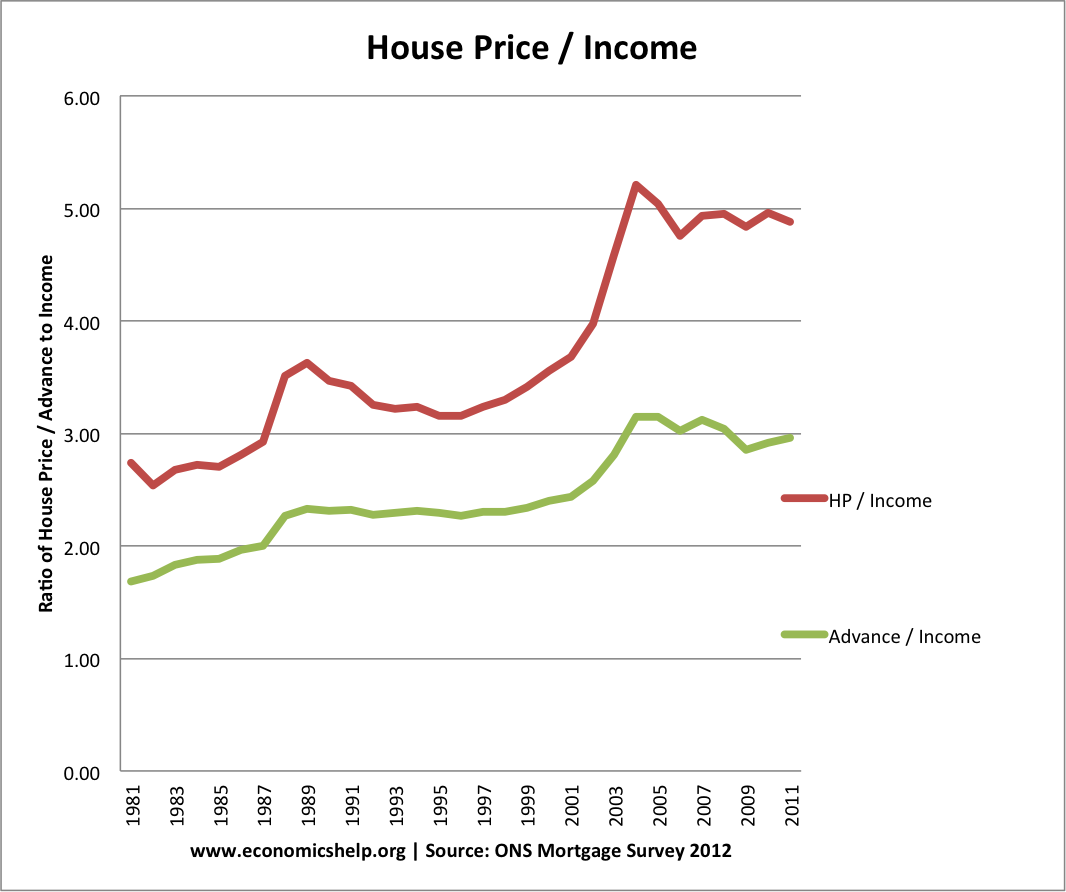

Many economists are sceptical of the belief in ‘the trickle-down’ effect. One reason, the wealthy have a higher marginal propensity to save, and also n recent years, wealth has been saved in off-shore accounts to avoid paying tax. Therefore, when the wealthy gain extra income, only a small percentage may filter through to low-income workers.

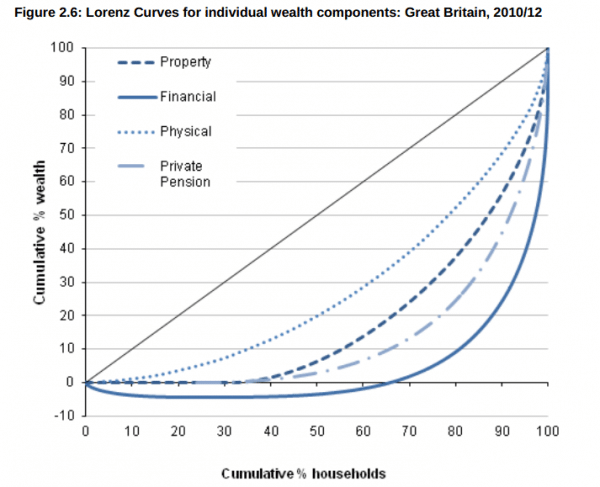

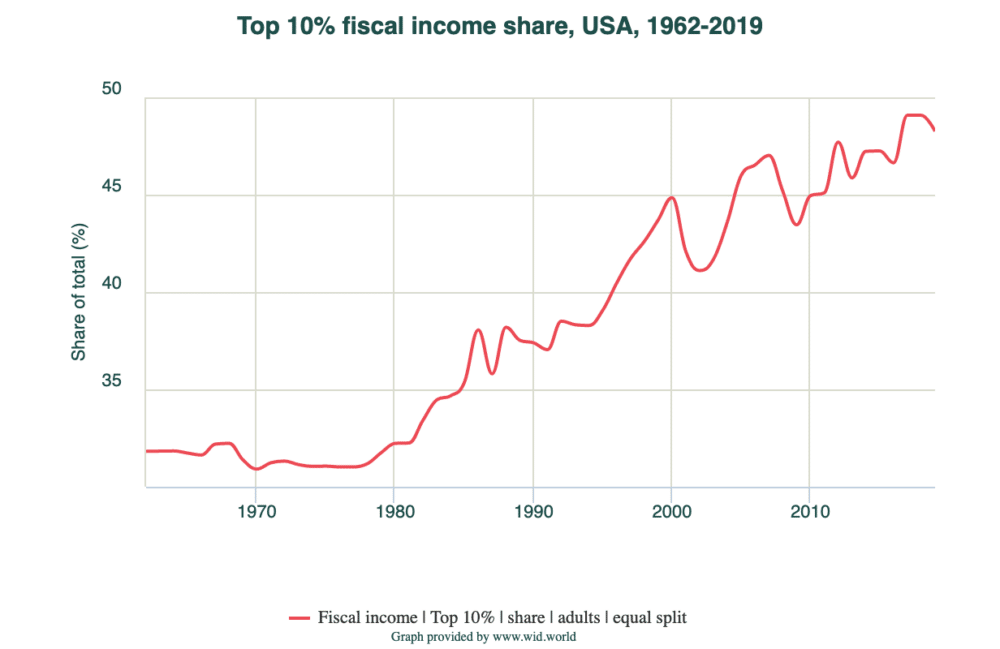

Also, some studies suggest that increased income inequality can lead to this inequality being solidified through educational opportunities, wealth accumulation and the growth of monopoly/monopsony power. Furthermore, increased inequality may lead to lower rates of economic growth.

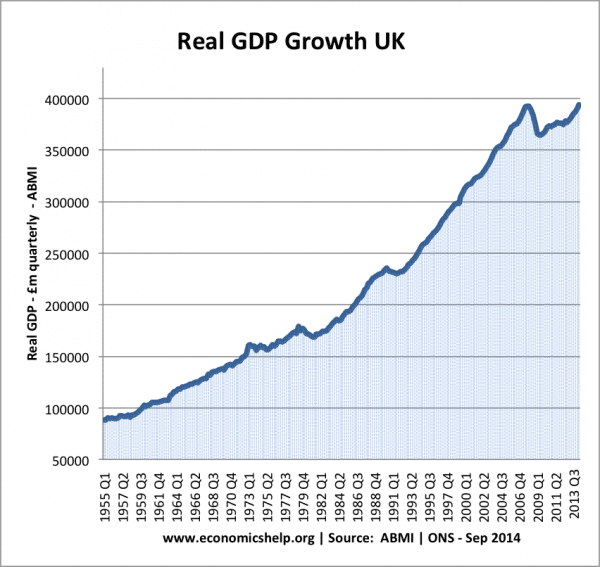

Tax cuts have no clear impact on growth. In The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich (2020), by David Hope and Julian Limberg, the authors found tax cuts for the rich, had no statistical effect on economic growth. They looked particularly at the 1980s in UK and US, where significant taxes were cut.

“The results also show that economic performance, as measured by real GDP per capita and the unemployment rate, is not significantly affected by major tax cuts for the rich. The estimated effects for these variables are statistically indistinguishable from zero.” (LSE)

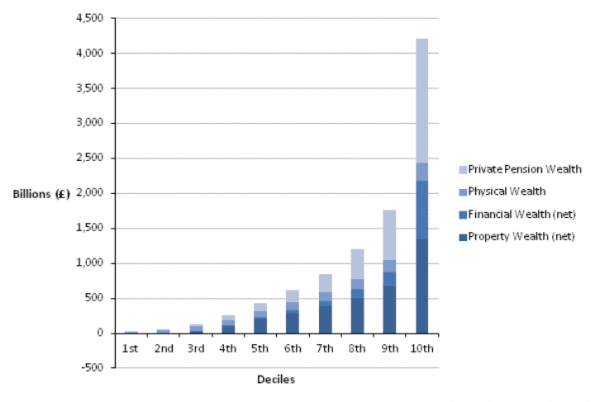

A report by the IMF (2015) found increasing income share of the poor increased economic growth, but increasing income share of the rich, led to lower growth.

“We find that increasing the income share of the poor and the middle class actually increases growth while a rising income share of the top 20 percent results in lower growth.”

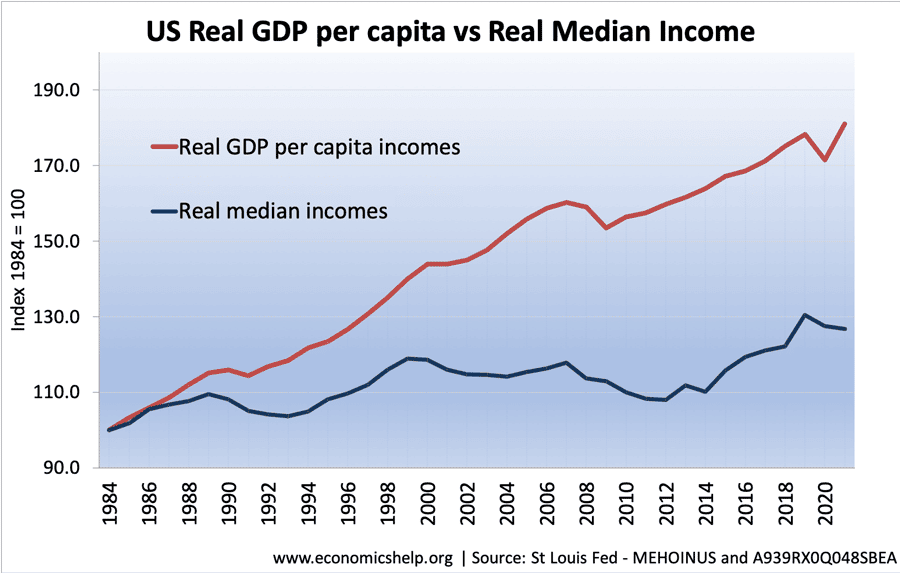

Real GDP and Median wages in the US

In the US, real GDP has grown faster than median wages since the early 1980s. In the 1980s, taxes were cut for high earners and there was a significant increase in inequality. Proponents of the Reagan tax cuts and supply-side economics argue it was worth it because everyone benefitted from rising GDP. However, the median wage, (which is the wage the middle-income earners actually receive has increased slower than real GDP, suggested not all the gains of the top 1% have trickled down to average workers.

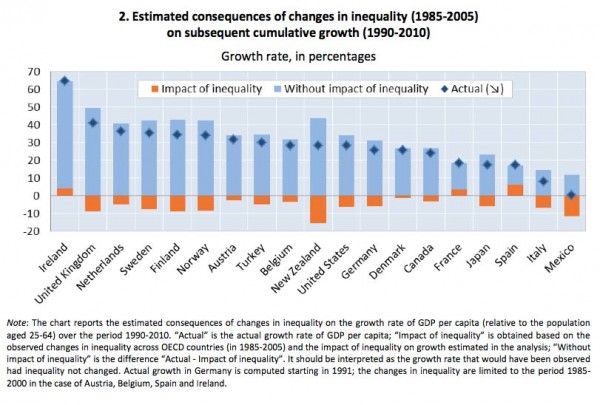

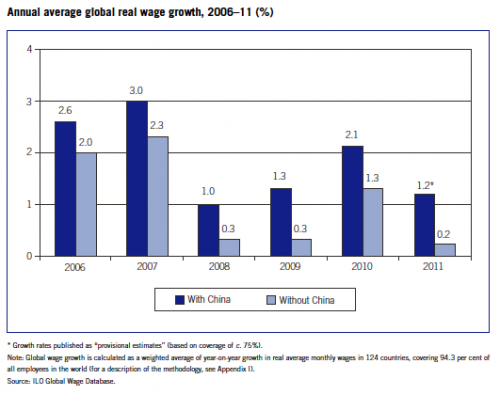

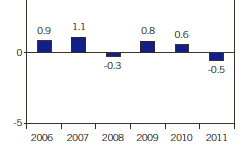

Inequality and lower growth. A recent report by the OECD found that since the start of the credit crisis in 2008, inequality has widened in many countries; however, this inequality has led to lower rates of economic growth not higher.

This graph from an OECD report suggests that inequality is responsible for lower GDP. The OECD estimates that the UK economy would have been more than 20% bigger had the gap between rich and poor not widened since the 1980s.