Inflation targeting means Central Banks are responsible for using monetary policy to keep inflation close to the agreed target (usually around 2%).

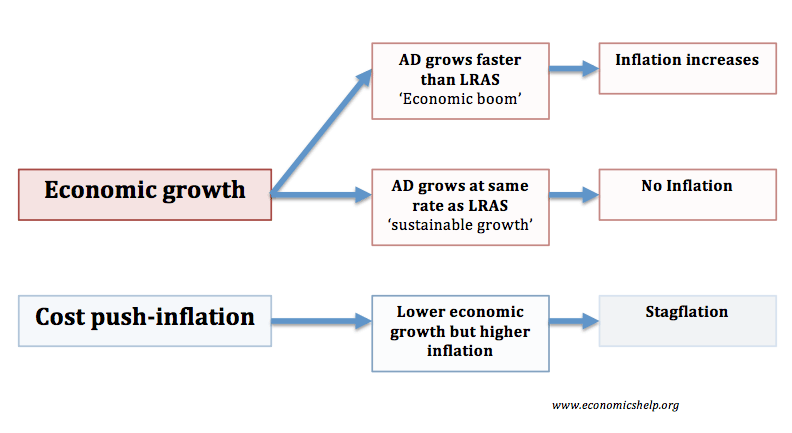

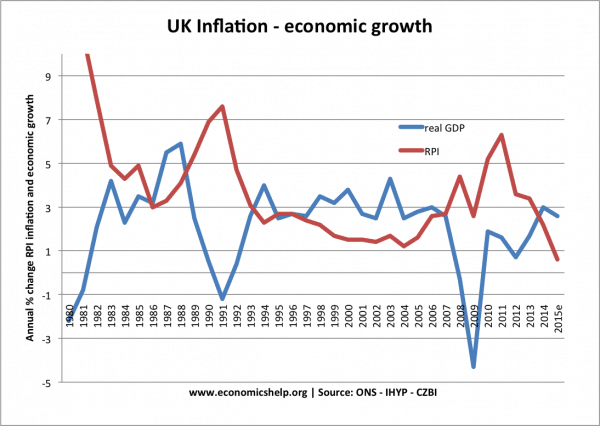

Since the mid-1990s, inflation targeting has become widely adopted by developed economies, such as UK, US, and the Eurozone. Inflation targets were introduced to help reduce inflation expectations and help avoid the periods of high inflation which destabilised economies in the 1970s and 80s. However, since the recession of 2008, economists have begun to question the importance attached to inflation targets and are worried that a strict commitment to low inflation can conflict with other more important macroeconomic objectives.

Inflation Targets

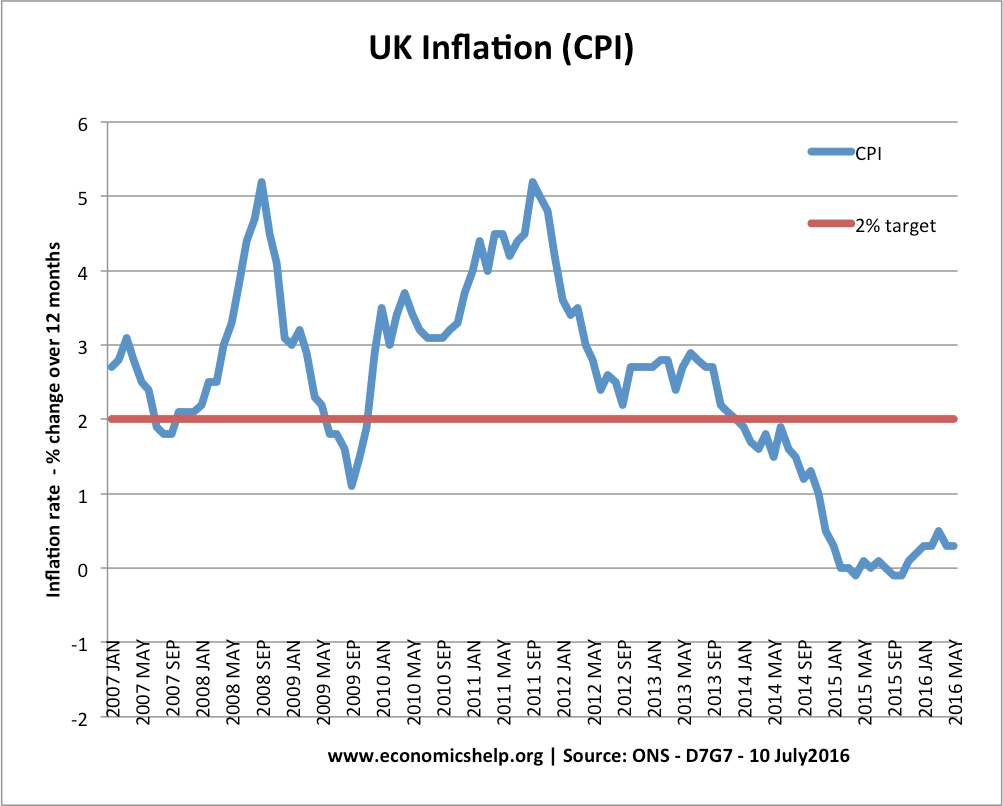

- UK. The Bank of England has an inflation target of CPI = 2% +/-1. They also have a remit to consider wider macroeconomic issues such as output and unemployment

- The ECB has a target to keep inflation below, but close to, 2%

- The US Federal Reserve has a dual target to keep long-term inflation at 2% and maximise employment.

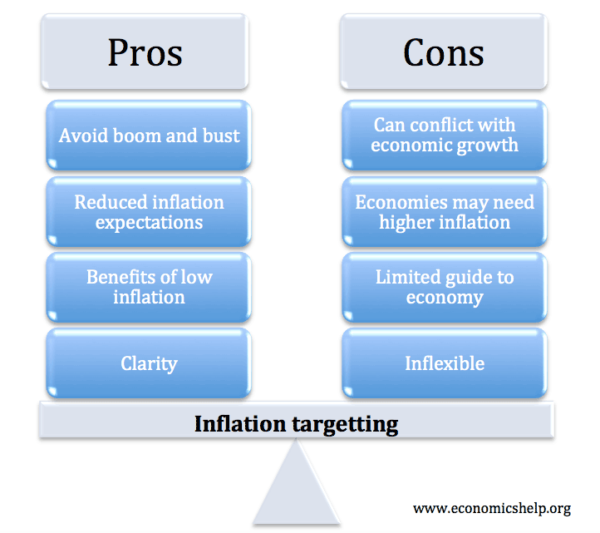

Benefits of Inflation Targets

- Credibility / Expectations. If an independent Central Bank makes a commitment to keep inflation at 2%, people will tend to have lower inflation expectations. Low inflation expectations make it easier to keep inflation low. It becomes a self-reinforcing cycle – if people expect low inflation, they don’t demand high wages; if firms expect low inflation, they are more conscious of increasing prices. WIth low inflation expectations, smaller changes in interest rates can have a bigger effect.

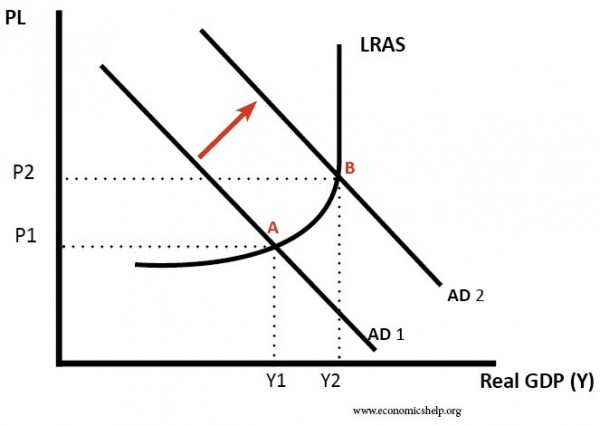

- Avoid Boom and Bust. The UK economy has suffered from many ‘boom and bust’ economic cycles. We had a period of high inflationary growth, which later proved unsustainable and led to a recession. An inflation target places a greater discipline on monetary policy and prevents monetary policy becoming too loose – hoping there has been a ‘supply side miracle. For example, in the late 1980s, inflation was allowed to creep upwards due to high growth – but this led to the bursting of boom and the recession of 1991/91. (See: Lawson Boom)

- Costs of Inflation. If inflation creeps up, then it can cause various economic costs such as uncertainty leading to lower investment, loss of international competitiveness and reduced value of savings. By keeping inflation close to the target, it avoids these costs and provides a framework for sustained economic growth. See: Costs of inflation for more details

- Clarity. An inflation target provides clarity for monetary policy. Alternatives have been tried with less success. For example, in the early 1980s, monetarism suggested trying to target the money supply – but this indirect targeting of inflation proved limited as the link between the money supply and inflation was weaker than expected.

Problems with Inflation Targets

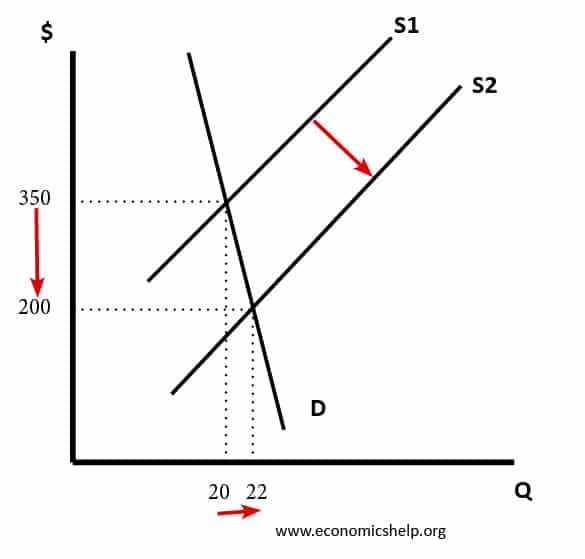

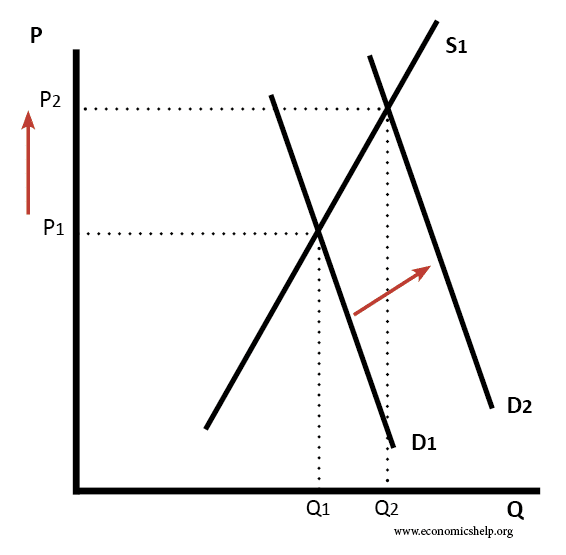

- Cost-push inflation may cause a temporary blip in inflation. Just before the recession of 2009, the UK experienced cost-push inflation of 5% due to high oil prices. To target 2% inflation would have required higher interest rates, which leads to lower growth. Some economists argued interest rates should have been cut earlier, and inflation targets were a reason for the delayed easing of monetary policy.

- To some extent, the UK and US are willing to tolerate temporary deviations from the inflation target. The Bank of England allowed inflation to be above target during 2009-2012 because it felt the inflation was temporary and the recession was more serious.

- However, the ECB have shown greater inflexibility and unwillingness to tolerate temporary blips in inflation. For example, in 2011 the ECB increased interest rates, despite low growth because they were concerned about inflation. The ECB then struggled with deflationary pressures.

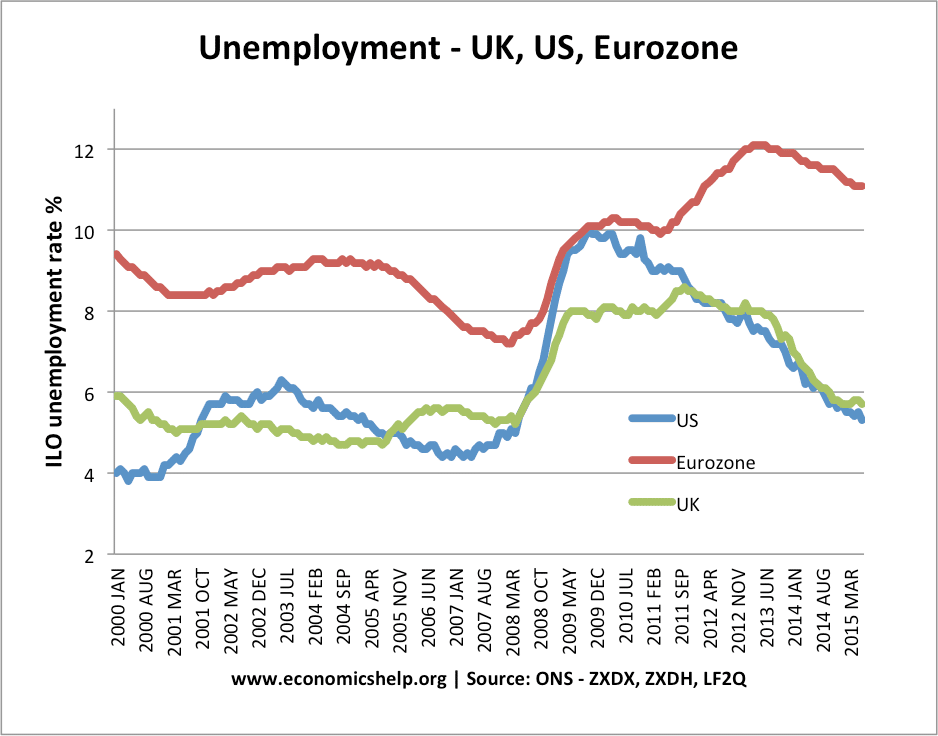

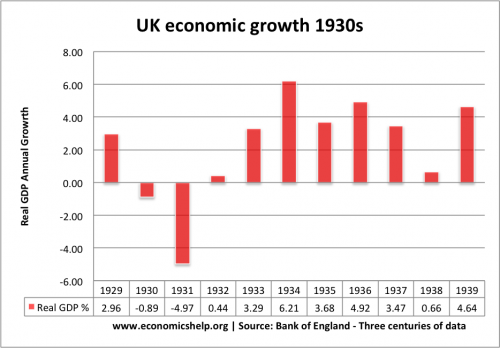

2. Central Banks start to ignore more pressing problems. The ECB set monetary policy to keep inflation in the Eurozone on target. Yet, by targetting inflation, they appeared to be downplaying the costs of rising unemployment. In 2011/12, the ECB seemed remarkably unconcerned about the Eurozone’s slide into a double-dip recession. Rather than trying to prevent a prolonged slump, they were fixated on the importance of low inflation.

Inflation above target can impose costs on the economy such as uncertainty, loss of competitiveness and menu costs, but arguably these costs are much less significant than the social and economic costs of mass unemployment. Unemployment in Spain reached 25%, but there was little monetary stimulus in the Eurozone because the ECB is worried about inflation at 2.6% – This is giving low inflation too much priority in times of a recession.