Firstly, I thought it might be helpful to talk about the different types of spending cuts that people refer to.

- An actual cut in government spending. e.g. one year we spend £39bn on defence, the next year that is cut to £38 bn. This is a nominal cut of £1bn. The real cut will be even bigger.

- A cut in real government spending. If inflation is 3% and government spending on education rises by 1%, that is a real cut of 2%. Departments will still have to cut back on wages and spending because with inflation higher than spending rises, they can afford less spending. It is fair to call this a spending cut

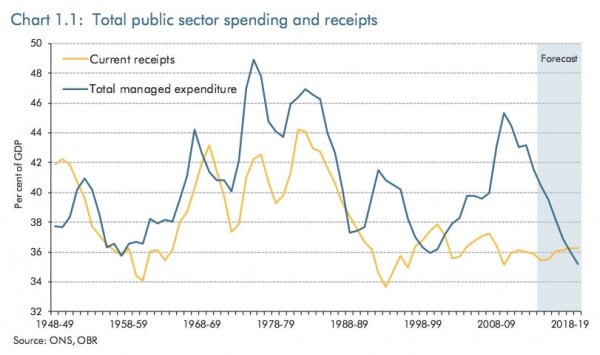

- A cut in % of real GDP

Suppose, real GDP rises by 3%, but one department sees a rise in real spending of 1%. In this case, the department has a smaller share of national income, but at the same time has a real increase in the amount of money. This isn’t a cut in government spending, but it is cutting the share of GDP spent on that department.

- A cut in quality of services. This is even more subjective. Suppose economic growth is 3% a year, but we increase the NHS budget by 4%. This is a real increase, and we are spending a higher % of national income on health. However, some may argue the demand for health care is rising by 8% a year due to rise in number of old people, rise in obesity e.t.c. Therefore, unless we match the demand for rising health care, it will lead to a cut in the quality of service and a rise in waiting lists. It is disingenuous to call a 4% real rise in spending a cut, but people’s experience of the NHS may feel like they are experiencing a cut.

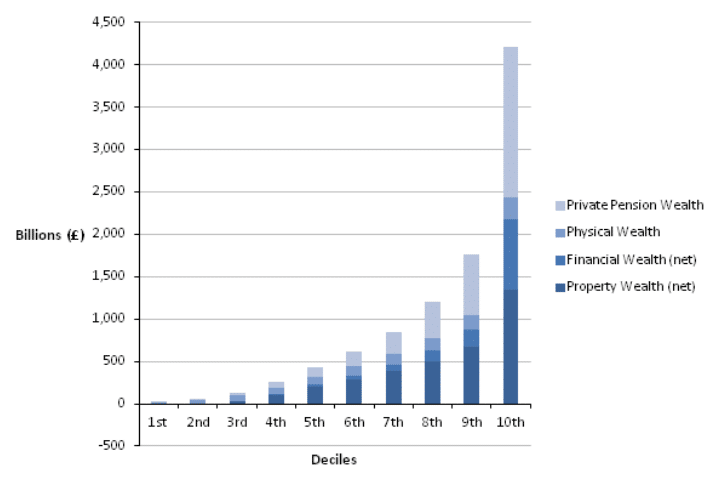

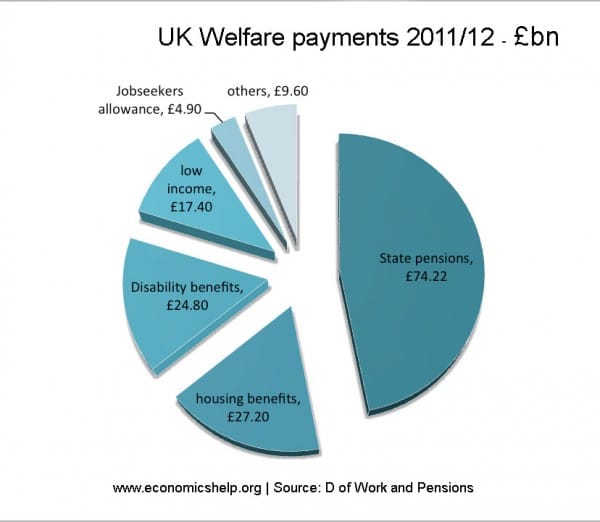

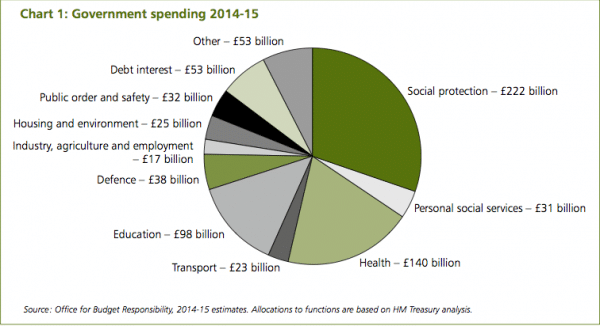

Government spending as a pie chart

Which piece of pie should be cut?