I’m currently writing a 2,500 word essay on ‘UK Austerity’ for the magazine Economic Review. I think the idea of these magazine articles is to present a ‘balanced view’ so I’ve been looking up the case for austerity as well as the case against. As far as I can see the economic rationale for austerity includes some or all of the following:

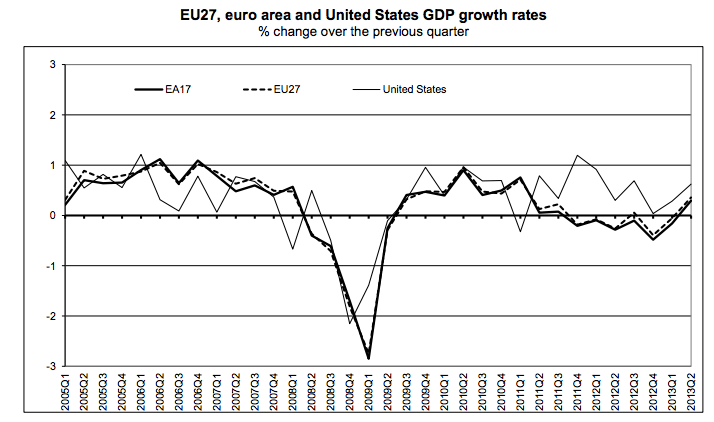

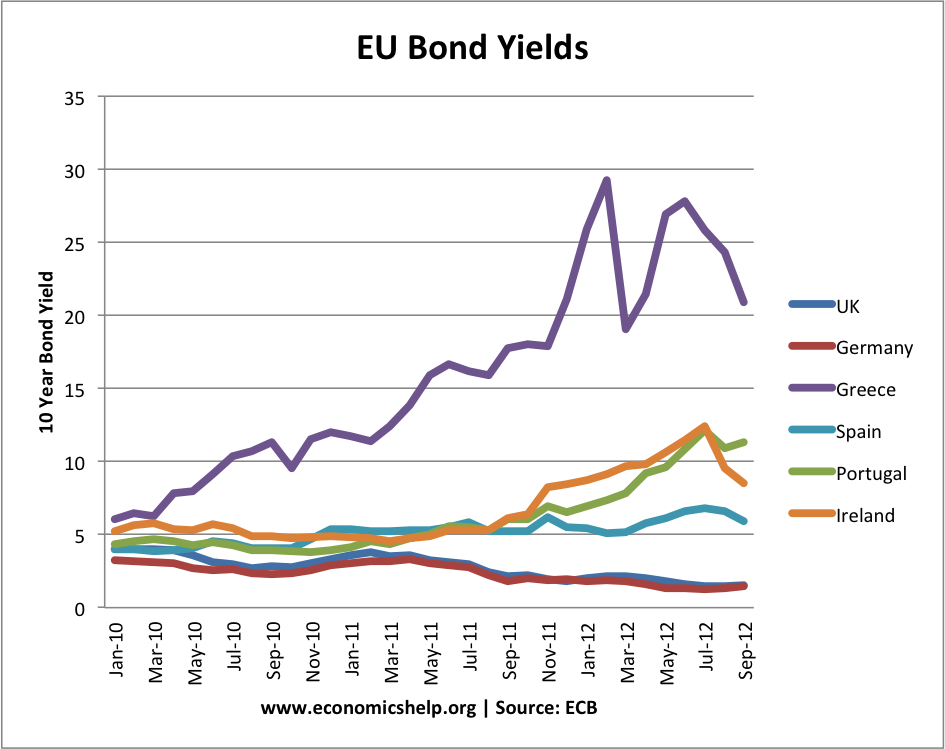

1. Rising bond yields. Starting with Greece, several Eurozone economies faced sharply rising bond yields in the period 2009-12. Investors were no longer confident in the ability of European countries to repay government debt or at least stay liquid. Therefore, they demanded higher bond yields in compensation for the increased perceived risk.

Rising bond yields were taken as a sign that debt levels were too high and unsustainable. Therefore, to reassure bond markets, governments pursued austerity / spending cuts to reduce budget deficits and hopefully reduce bond yields.

In the case of the UK, the government argued that if Greece, Ireland and Italy could all have rising bond yields, the same could happen to UK bonds. If government bond yields did rise, the government argued it would have many adverse consequences for the economy:

- Increase cost of debt interest payments.

- Make it difficult to sell sufficient bonds to cover the large budget deficit.

- Rising bond yields can create a knock on panic to other bond investors. The nervousness was potentially contagious.

2. Crowding in. There is a view that if the government reduces spending and reduces government borrowing, then this enables a growth in the private sector. The argument is that government borrowing restricts private sector investment because when the government borrows it takes money which could be used to finance private sector investment.

3. ‘Expansionary austerity’ This was a view offered at the start of the crisis. The argument is that uncertainty over rising bond yields was holding back private sector investment. If the government pursued austerity and proved to the market it was serious about reducing the deficit and bond yields, markets would be more confident about the future. The sound money of the government would encourage private sector investment and higher economic growth.

4. State is too big. Mixed up in the case for austerity is the more general argument that state spending had got too big. The recession was seen as a good time to cut away inefficient government spending. In particular, some economists were critical of the bloated size of the welfare state and pension commitments. Often critics of Keynesian economics argue that if you pursue temporary spending to boost demand, this temporary stimulus ends up being permanent, due to special interest groups. Instead, the opposite should occur, and governments should take the opportunity to cut spending.

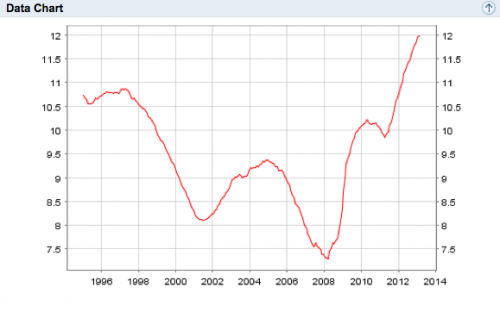

5. Debt is too high. The credit crunch was caused by banks taking on too many ‘bad’ debts. Because the excess accumulation of private sector debt caused the credit crunch and recession, it was easy for governments to make a link that we need to tighten belts and reduce government debt burdens.

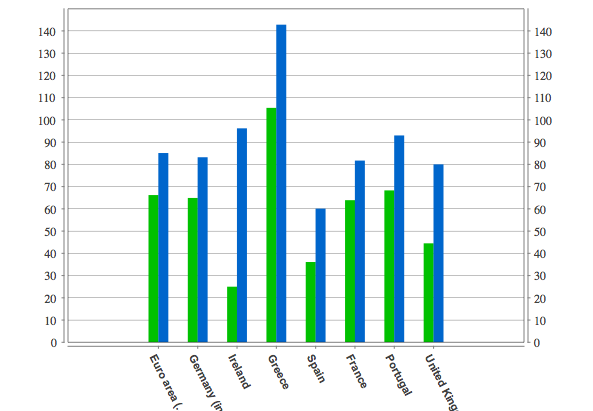

EU debt levels debt / GDP % 2007 – 2010

e.g. Ireland debt to GDP ratio rose from 27% to 97% between 2007 and 2010

In the great recession, budget deficits did rise rapidly because of the fall in tax revenues due to recession, rise in welfare spending due to unemployment, and bailing out banks.

One influential paper (2010) by Carmen Reinhart, now a professor at Harvard Kennedy School, and Kenneth Rogoff, an economist at Harvard University, suggested that when debt / GDP levels rose above 90%, then it leads to significantly lower economic growth. (90% question at Economist) Therefore, this provided an argument for tackling government debt.

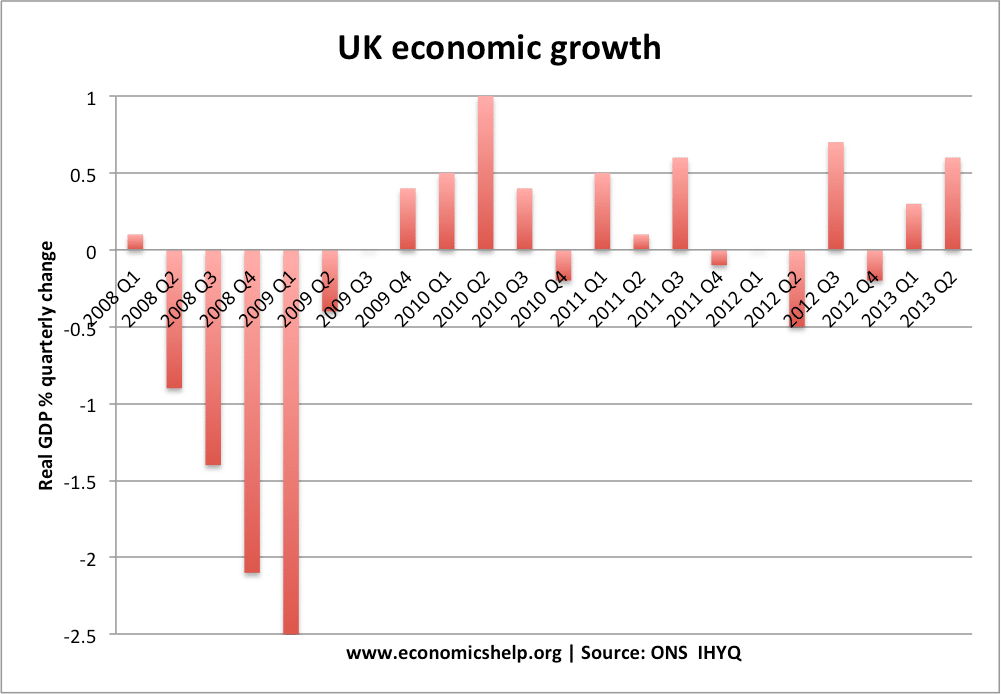

6. Countries with austerity have had positive growth

Every country which pursues austerity has at some time seen economic recovery. Latvia experienced a strong recovery (after very sharp fall in GDP during the recession.) Now positive growth in UK is seen as vindication of austerity.

Criticism of Austerity

A quick evaluation to these points

1. Rising bond yields. The assumption was that rising bond yields were due to high levels of debt. But, with perhaps the exception of Greece, rising bond yields were primarily due to having no Central Bank willing to act as lender of last resort. Evidence for this comes from:

- Countries like US and UK with very large budget deficits saw falling bond yields during the recession. These countries had own currency and Central Bank willing to ensure liquidity.

- In 2012, when the ECB finally became willing to buy unlimited bonds, bond yields fell sharply.

- Austerity policies often caused bond yields to rise because markets feared falling GDP would make debt levels more unmanageable.