Readers Question: How sustainable do you think that the austerity measured imposed on European countries are in economic and political terms?

This is a good question. Firstly, I feel there is a certain political appeal of austerity. See: Why is austerity politically popular?

When austerity was introduced, there was a reluctant support for austerity – because of the widely disseminated view it was necessary. However, as time passes and austerity appears to have given more pain than gain, the political support will continue to dwindle.

A politician promising to ‘get tough on debt’ has a certain political capital. A politician promising to bring in counter cyclical budget policies is (firstly, is very rare) and also likely to get ignored or mis-understood. There is growing criticism of austerity, but it is a rare to hear a politician talking about – targeting full employment, running a bigger cyclical deficit and / or monetising debt.

There are a few issues:

Unemployment is a marginalised political issue

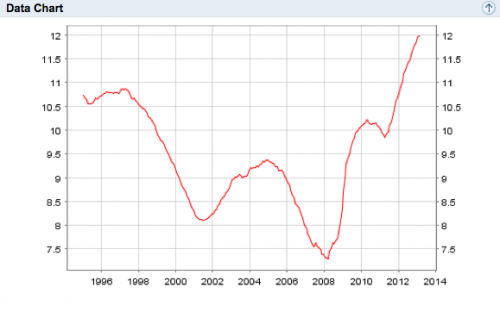

In my opinion, unemployment is one of the greatest personal finance disasters and one of biggest economic / social problems facing society. It is not just a loss of income, but also a loss of self-esteem because you don’t have the opportunity to contribute to society. But, there never seems to be the same political urgency to tackle high unemployment. When the Coalition government was elected in 2010, the impression I got is that they were more concerned with reducing the budget deficit than tackling unemployment.

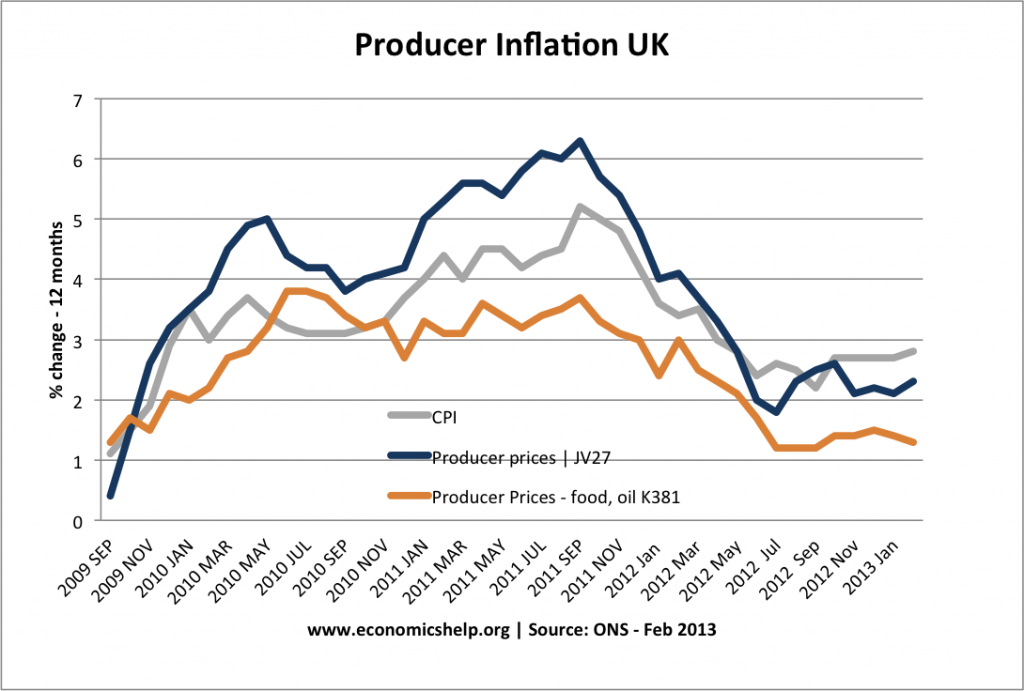

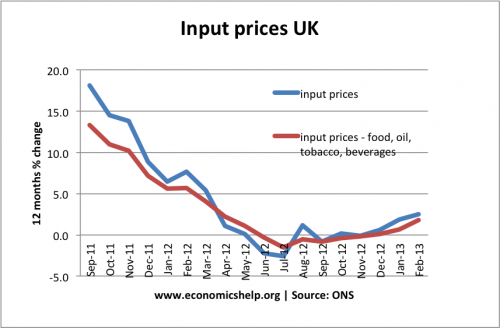

The ECB seem to live in a bubble where they define economic success as achieving an increasingly meaningless inflation target, budget deficit reductions and lower bond yields.

However, with unemployment rates in Europe continuing to increase, it may become a bigger issue amongst the electorate. If European policy makers don’t engage with the unemployment issue, there may be an increased gap between the unemployed and policy makers.

Austerity hasn’t worked

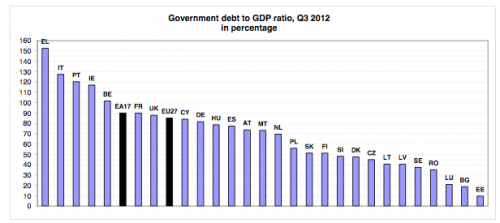

Generally, a temporary rise in unemployment and fall in GDP can be shrugged off. However, the problem with the austerity policies of the last few years, is that they have left Europe in continued difficulty. Even by a very narrow view – measuring success by debt to GDP targets, it has often failed (Austerity self-defeating). Some of the worse affected countries like Greece, Italy and UK are failing to stop the rise in debt to GDP.

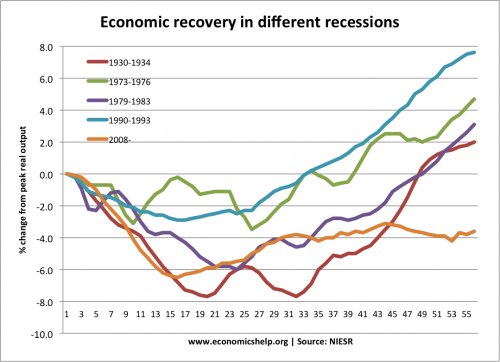

But, in the bigger picture, austerity and monetary inflexibility are contributing to a significant double dip recession. Unemployment for 6 months is one thing, but a rise in long-term unemployment is much more serious.

The problem Europe faces is that it is hard to see where strong economy recovery is going to come from. With tight monetary, tight fiscal policy and fixed exchange rates, there is an inertia – preventing economic recovery and reducing unemployment. Even countries who don’t need to pursue austerity – Germany and Netherlands have embraced the trend for cutting spending. The consequence has been to push European growth lower. There is a real danger of a lost decade; we already have lost half a decade.