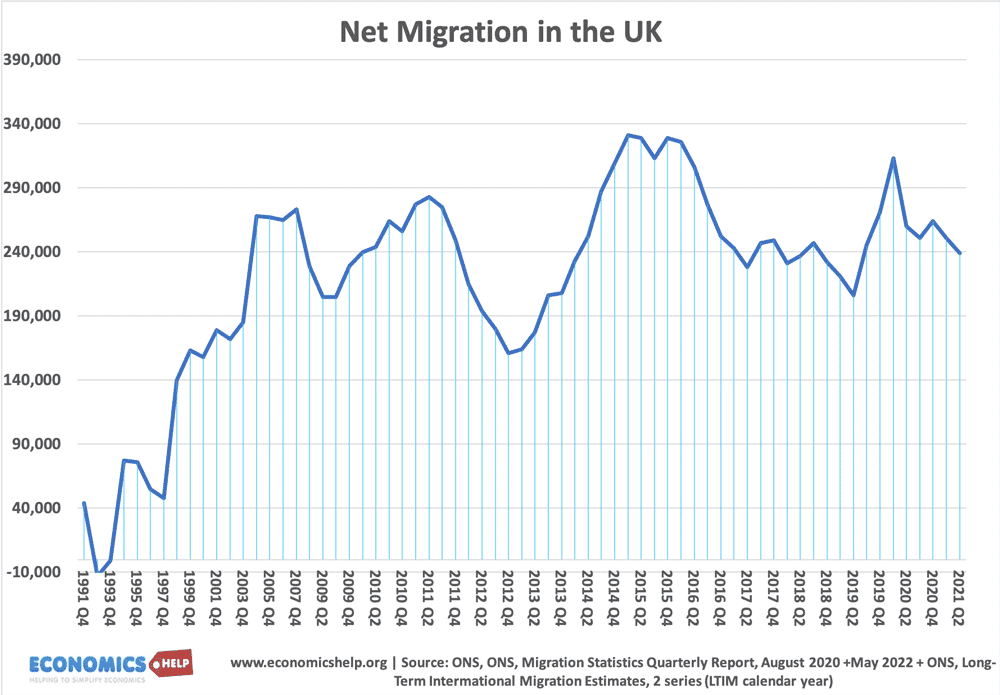

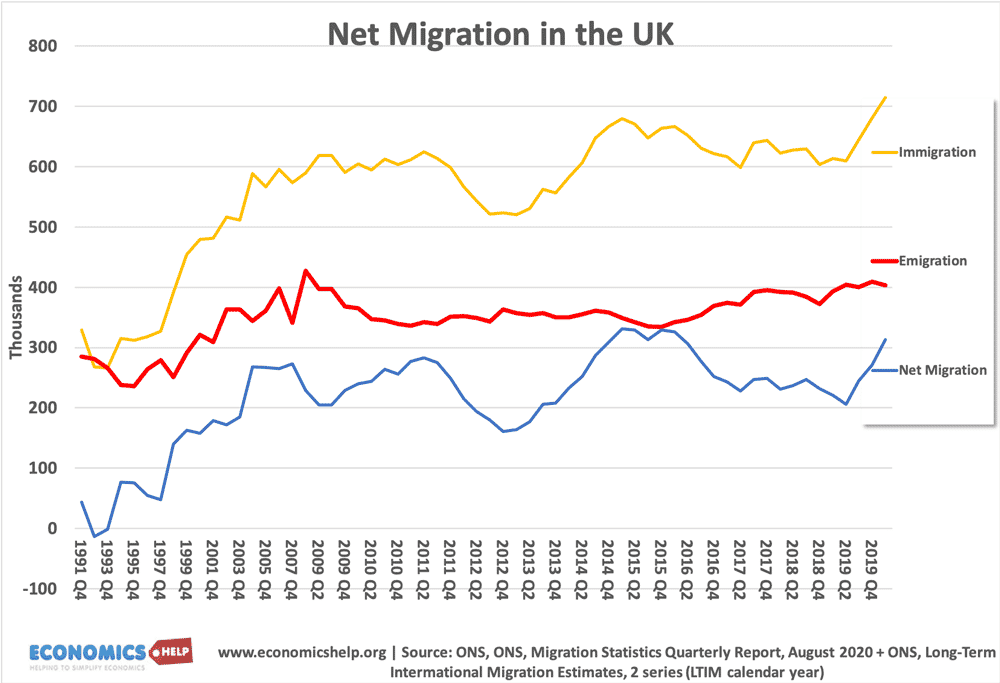

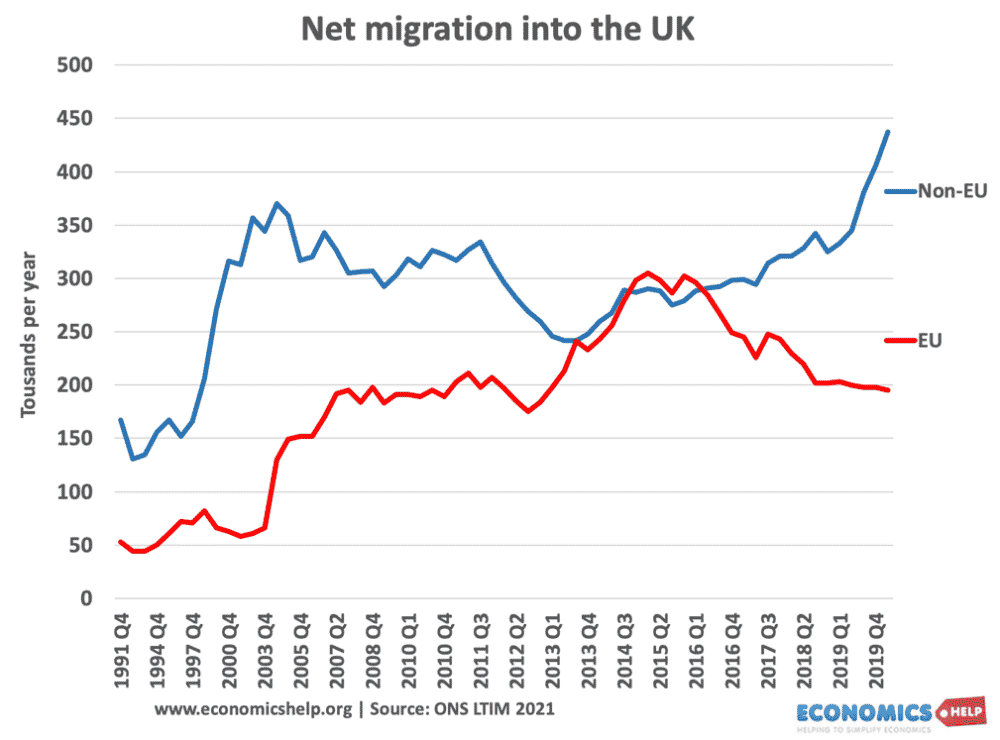

In the past two decades, the UK has experienced a steady flow of net migrants into the economy. The 2016 Brexit vote has led to a sharp fall in net EU migration, but to a large extent this has been offset by a rise in non-EU migration. This net migration has had a wide-ranging impact on the UK population, wages, productivity, economic growth and tax revenue. Does net migration benefit the UK economy?

- In 2021, Net long-term international migration was estimated to be +238,000 in 2016.

- In 2021 Q4, there were 18.766 applications for asylum.

- In 2019, there were 9.5 million people born outside the UK (estimated 14% of the UK’s population.) (5.8 million, non-EU, 3.6 million EU)

Inflows and Outflows

- In 2019, the top 6 countries for the source of migrants was India, Poland, Pakistan, Romania, Ireland.

EU vs Non-EU immigration

Traditionally non-EU immigrants are more likely to come for family reasons, whilst EU migration has been focused on work.

Impact of Net Immigration on UK Economy

1. Increase in Labour Force

Migrants are more likely to be of working age. The majority of migrants come for work or study (students) They may bring dependents, but generally net immigration leads to an increase in the labour force, a decline in the dependency ratio and increases the potential output capacity of the economy.

2. Increase in aggregate demand and Real GDP

Net inflows of people also lead to an increase in aggregate demand. Migrants will increase the total spending within the economy. As well as increasing the supply of labour, there will be an increase in the demand for labour – relating to the increased spending within the economy. Ceteris paribus, net migration should lead to an increase in real GDP. The impact on real GDP per capita is less certain.

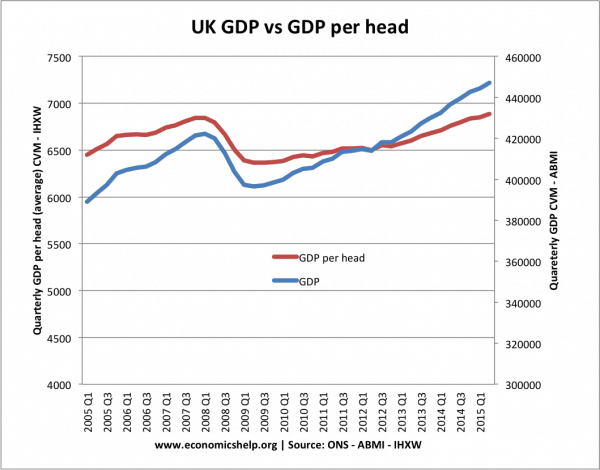

In fact, net migration can make economic growth look stronger than it is. In the period 2005-2015, UK real GDP has increased significantly faster than GDP per head. See GDP per capita for more info.