Readers Question: You have partially explained the answer to my question in your reply to my other question, “What will we do when we can’t pay back the money owing to the government bond holders when they reach the end if their term”. While I appreciate the convenient use of the debt to GDP ratio I feel that it tends to sidestep the truth about the remaining debt. This is almost like the government using the reduction in the deficit rather than the reality of remaining, possibly increasing debt.

For some reason, the first thing that comes into my mind is the famous quote from Dr Strangelove – “how I learned to stop worrying and love the bomb (debt)”

I guess we can blame Charles Dickens and Wilkins Micawber from David Copperfield.

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery.”

No matter how much you talk about government debt, people won’t feel comfortable until we have a zero budget deficit and zero government debt. – (even though, I don’t think any modern economy has ever had such a situation – nor would one be particularly desirable.) Many issues are addressed here: The political appeal of austerity.

What does debt cost?

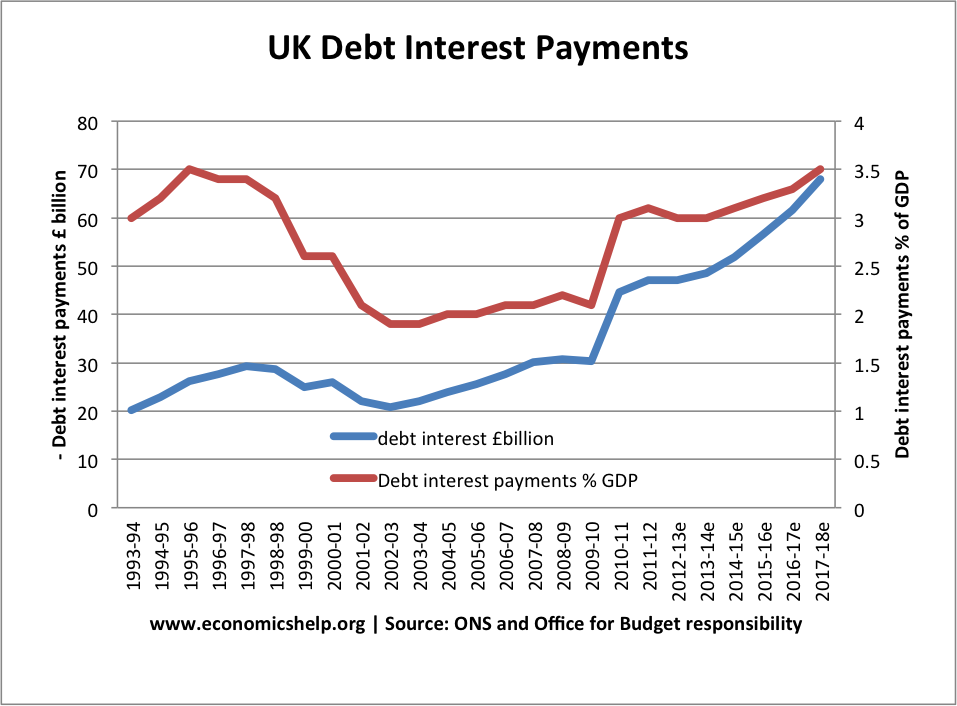

Another way of thinking about government debt is the annual cost of servicing the debt. What percentage of GDP is spent on debt interest payments? What percentage of tax revenues is spent on servicing the debt? You could have an increase in the real value of debt, but a smaller percentage spent on paying interest on the debt. Would you worry about a mortgage – if every year the monthly mortgage payments were becoming a smaller percentage of your disposable income?

The cost of servicing UK debt has risen in the past few years, due to rise in debt. But, by historical standards, it is still quite low and certainly quite manageable. More on Cost of borrowing

Of course, the cost of debt interest payments also depend on interest rates. A rise in interest rates will cause higher borrowing costs. But, with low interest rates predicted, we are unlikely to see a jump in borrowing costs – at least in the medium term.