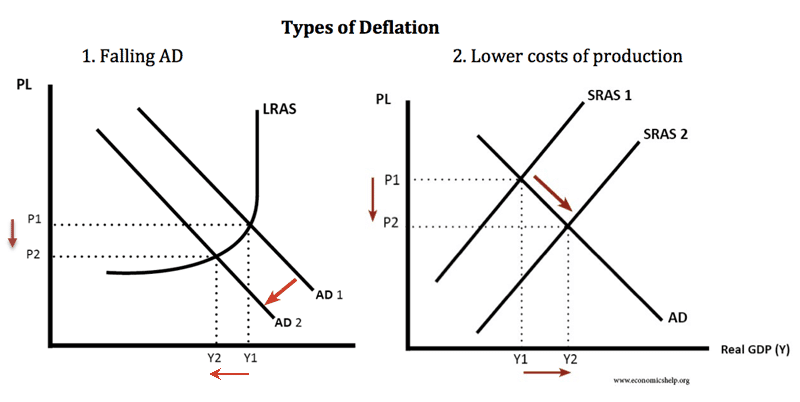

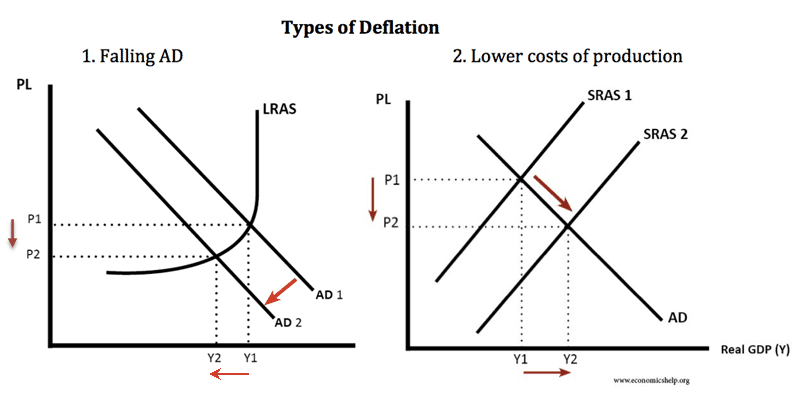

Is deflation good or bad? Mostly experiences of deflation in western economies have been damaging – deflation has been associated with falling rates of economic growth and higher unemployment. However, it is possible to have a different type of deflation – from rapidly improving productivity; then deflation can be consistent with higher rates of economic growth.

Deflation caused by lower costs ‘good deflation’

If we have ‘good’ deflation – due to a big increase in productivity, lower costs – then in theory firms will be able to pay real wage increases. With this type of deflation, we are seeing lower prices, but also higher output, higher productivity, higher profits – and hopefully higher real wages. If consumers see lower prices, but they have rising real incomes, then you would expect higher spending because they will have the money to buy these cheaper goods.

Example of good deflation 1870-1890

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the US, UK economies benefitted from a worldwide fall in prices due to the “Second Industrial Revolution”. This included major improvements in productivity:

- More efficient steam engines

- Improved steel production (Bessemer Steel)

- Cheaper cost of railways – railways came of age.

- Improved communication.

- The transition from agricultural to industrial production.

The US economy grew rapidly in this period – benefitting from the new technology which helped lower costs. An important feature of this period was that although prices fell, wages were constant or rose and so workers saw real wage growth.

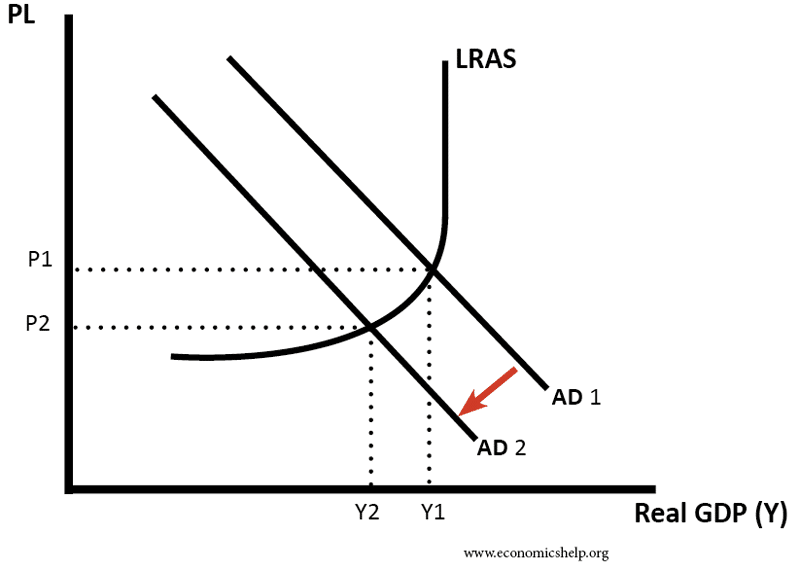

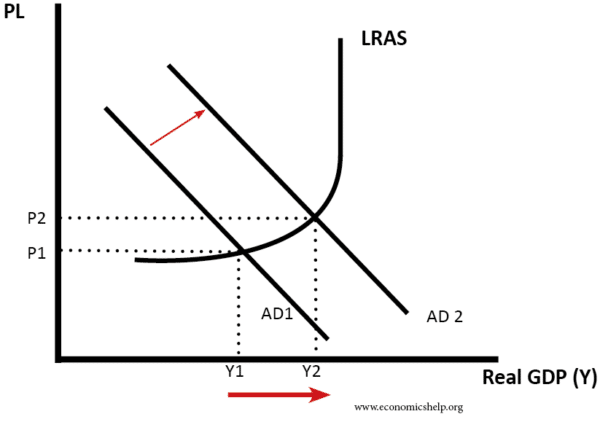

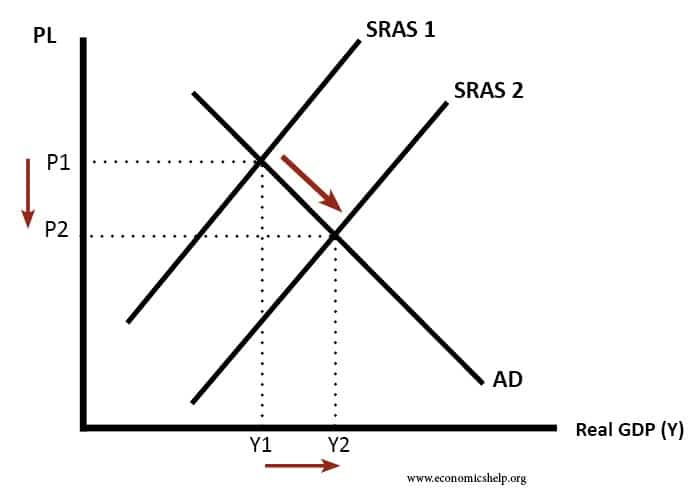

Deflation caused by falling demand

Deflation caused by a fall in AD.

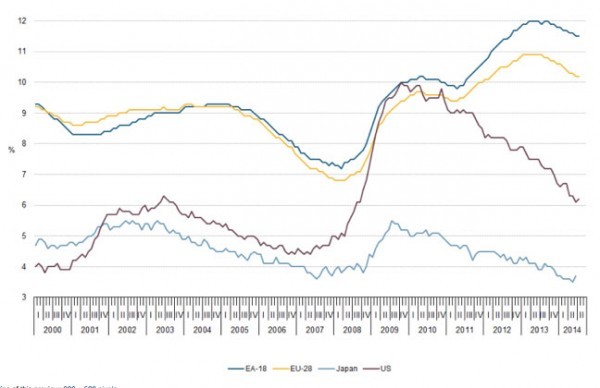

If we have ‘bad’ deflation – falling prices caused by weak demand, then firms will be seeing a decline in profitability. In this circumstance, firms will not be increasing wages but trying to cut wages. Also, if firms can’t cut nominal wages, we may see a rise in unemployment (a combination of real wage unemployment and demand deficient unemployment).

Therefore, in this scenario of lower wages / higher unemployment, the falling prices will not be sufficient to encourage spending and higher consumption. Instead, people will be risk-averse trying to save and waiting for prices to fall further.

Costs of deflation

If prices are falling but nominal wages are also falling or stagnant, we tend to get these problems.

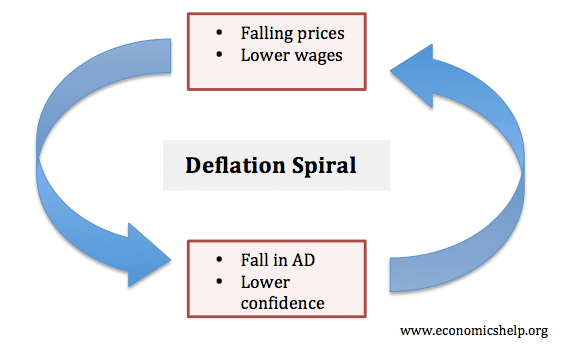

- Consumers delay purchases. With falling prices, consumers expect prices to be lower in the future, so put off purchasing goods.

- Rise in real value of debt. With falling prices and falling wages, it becomes harder to pay off debt and meet debt repayments.

- Real wage unemployment. With falling, prices firms can’t afford workers, but if workers resist nominal wage cuts, then there will be real wage unemployment

- Higher real interest rates. Interest rates cannot fall below zero, so if there is deflation, the effective real interest rate rises. Therefore, even if the economy is depressed, real interest rates are high – discouraging borrowing and encouraging saving.

- Deflationary cycle. In a deflationary cycle, lower demand leads to lower prices, and falling prices cause lower demand, it is a vicious circle.

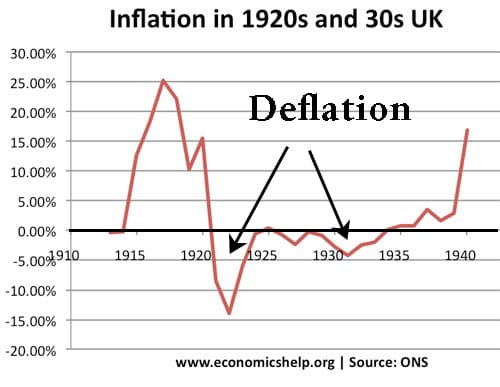

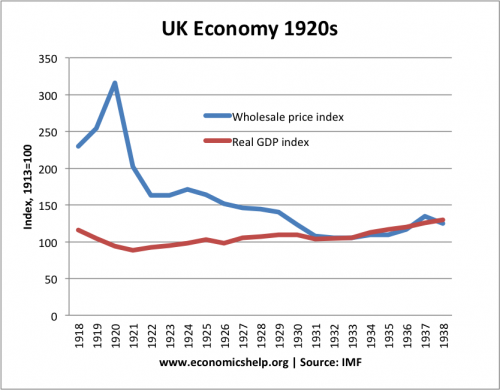

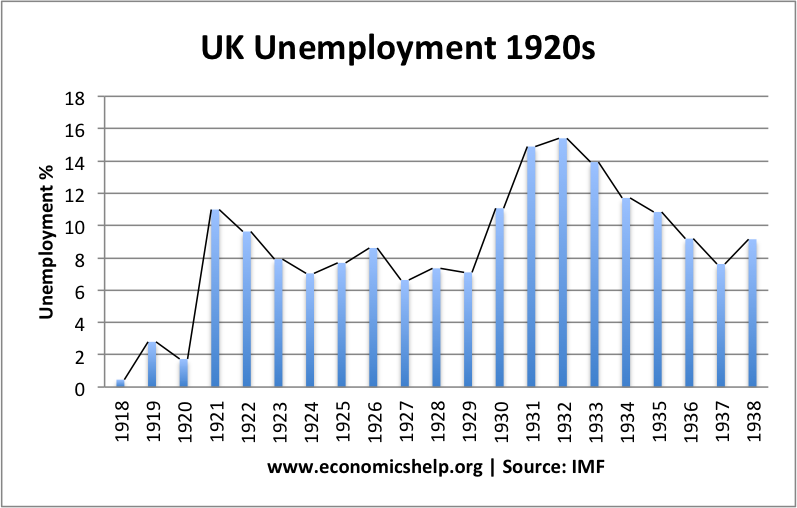

Example of ‘bad’ deflation – the UK in the 1920s and early 1930s

Unemployment high during the 1920s and early 1930s. See: UK economy in the 1920s

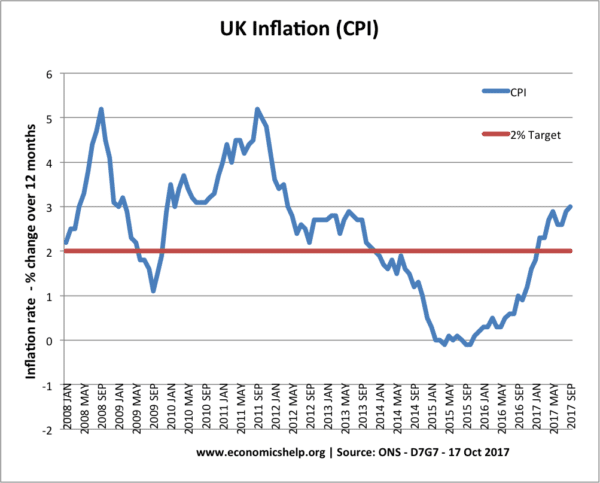

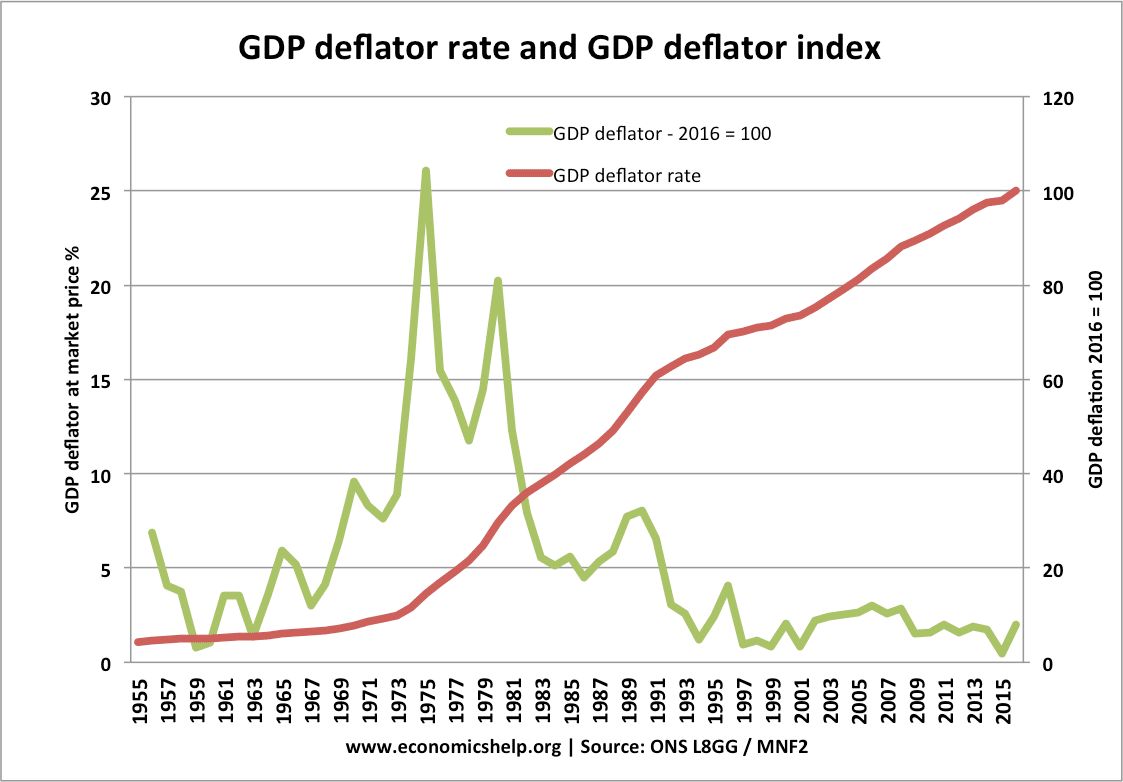

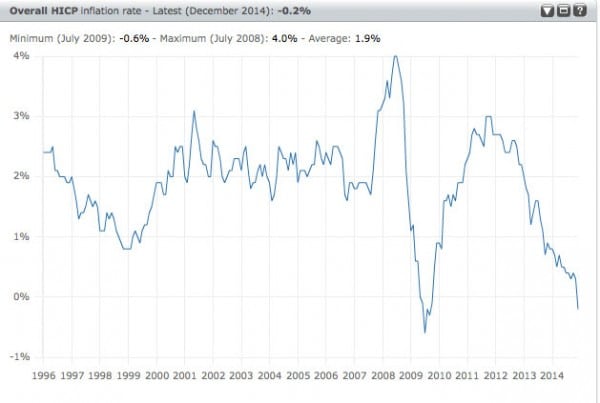

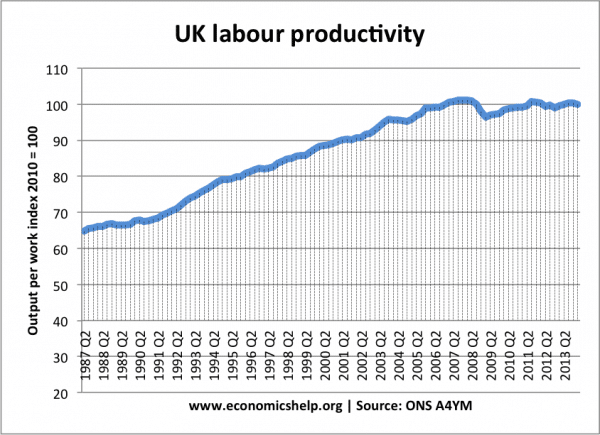

Deflation/low inflation of UK 2010s

Ignoring cost-push factors underlying inflationary pressures in the UK have been low – with inflation falling to zero in 2015. However, a significant reason for this deflation/low inflation is the poor productivity – and consequent stagnant real wages. Inflation is low, but households are becoming worse off.

Falling prices led to stagnant real GDP

Readers Question: And regardless of the reason, people should put off buying shouldn’t they?

It can depend on consumer confidence and expectations of future wages/employment opportunities. If we have a period of deflationary pressures – low /negative growth, then people may be fearful about future employment opportunities, they will expect low wage growth, and possibly unemployment – therefore, in this circumstances, consumers will be trying hard to be careful in budgeting and spending. If they think prices will fall and their income may decline, then this is an added reason to delay spending.

However, if there is strong growth, low unemployment and rising wages, there is much less need to be careful with spending – therefore, they will be willing to buy now and enjoy their rising real wages.