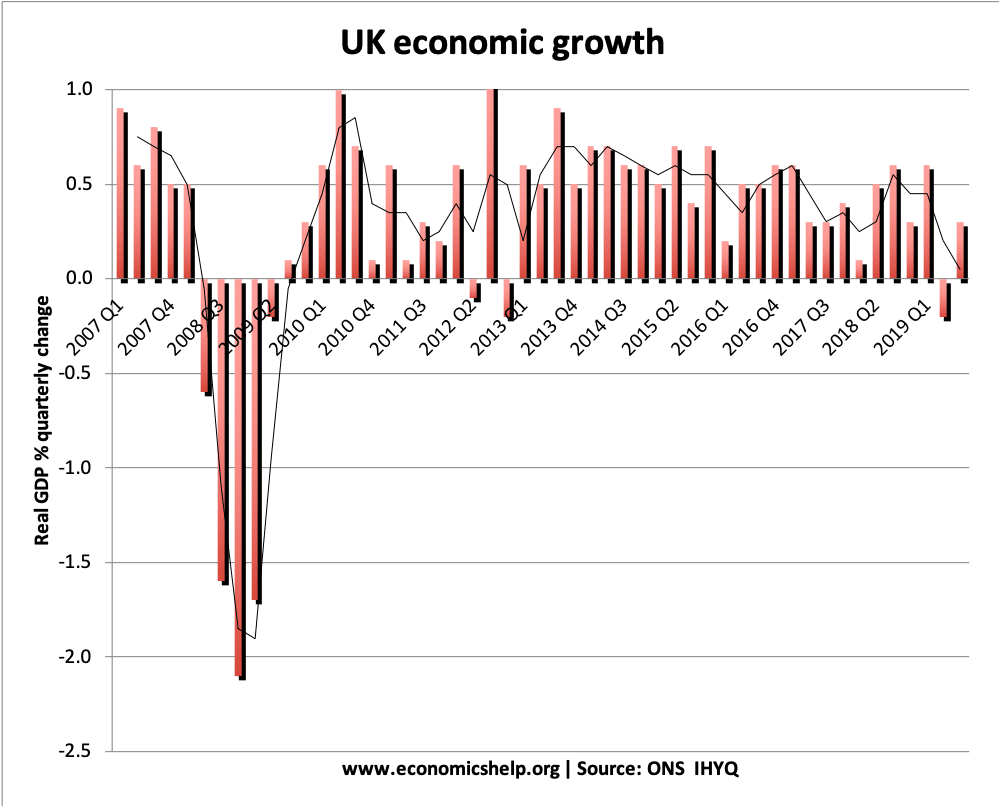

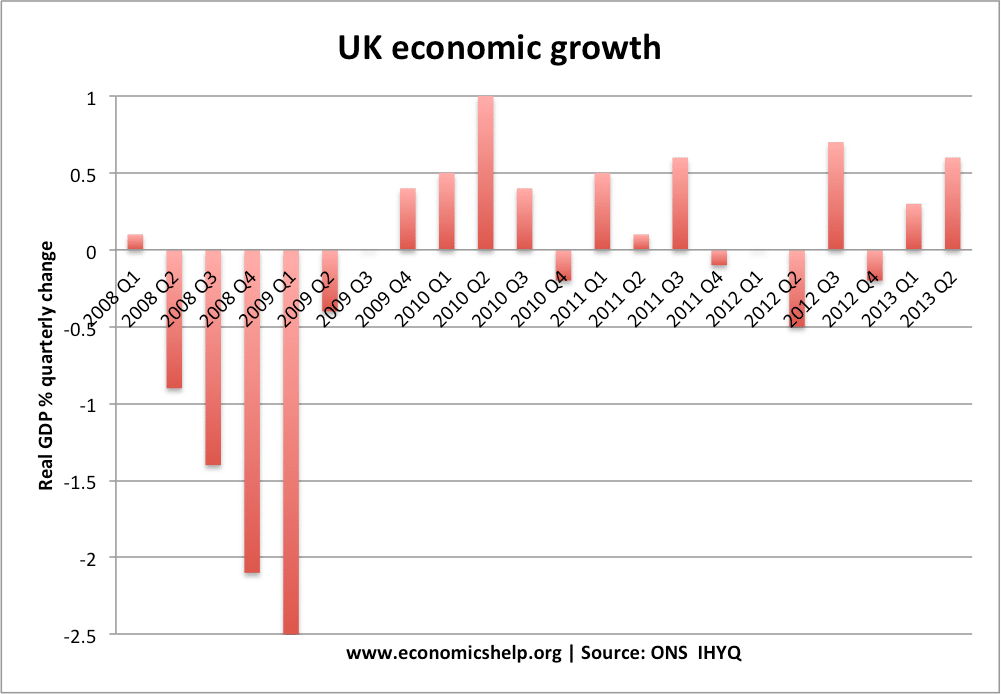

The UK economy has experienced the most prolonged decline in real GDP on record. GDP is still lower than before the start of the great recession in 2008. This unprecedented recession has been prolonged – despite a sharp depreciation in the Pound, and a raft of unconventional monetary policies. However, recent statistics suggest there are some reasons to be more hopeful and the UK economy is starting to recover. Yet, despite the recovery, many analysts still worry that the economy is unbalanced and could be vulnerable to a further economic downturn in Europe and the rest of the world.

Economic recovery

Source: ONS

The UK recovery since 2009 is best described as ‘patchy’ The important thing is to maintain recovery for a prolonged period and not slip back down into recession. The governor of the Bank of England recently talked about the need for the UK economy to reach ‘escape velocity’ – this means a recovery strong enough for the recovery to be self-maintaining – without the artificial props of quantitative easing e.t.c.

Where is the recovery coming from?

1. Retail spending. Although real incomes remain depressed, retail spending has shown renewed strength. Compared with a year ago (July 2013 compared with July 2012) the quantity bought in the retail industry increased by 3.0% (ONS). Consumer spending accounts for approx 65% of UK GDP and so is the most important component. A rise in consumer spending is good because it shows a renewed confidence about the economy. However, at the same time, it raises concerns. The growth in consumer spending is partly financed by a fall in the savings ratio, it isn’t being met by growth in real incomes. Therefore, there is a danger the UK recovery is falling into the old trap of being unbalanced and relying on consumers dipping deeper into their pockets (and credit cards)

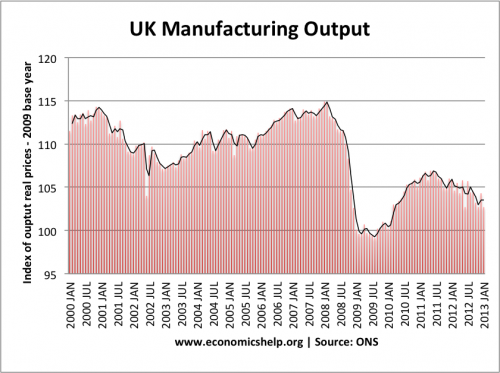

2. Manufacturing. For a long time, manufacturing has been the struggling sector of the UK economy. The weakness of manufacturing is one factor behind the UK’s persistent trade deficit, but recent evidence is more promising. This week, the PMI survey for the manufacturing sector found the strongest growth in activity for two and a half years, with output and new orders rising at their fastest rate for 19 years. However, although this sounds impressive, it needs to be remembered manufacturing output is still 11% lower than it pre- 2008 peak.

– a long way to recovery.

Construction has also seen growth in the first part of 2013, but, this is from a very weak base, and construction output is still down 0.5% on a year ago. (ONS)

3. Exports to emerging economies. In 2013, we have seen strong export growth to emerging economies. Exports to BRIC countries have performed well. Exports to China have risen nearly sixfold since 2002.

In one sense, these export growth to new markets is encouraging. With Europe stuck in recession, it is good news the UK exporting sector has been able to diversify into emerging markets, which perhaps have greater potential in the long term. However, there have been increasing concerns that the long boom years for China and India may be coming to an end. This would dampen growth in these new export sectors. Also, it is still a small share of GDP for the UK economy.

4. Housing Market. Another staple of the UK economy. A renewed rise in house prices is a mixed blessing. The rise in prices will encourage consumer confidence and improve the balance sheets of banks. It has also encouraged renewed activity in the construction sector. However, house prices are already stretched, with house price to income ratios close to all-time high. Rising house prices as the main source of economic recovery is another sign of an unbalanced economy.