Recently, the Economist published an article (You can fool some of the people…), pointing out several economic commentators were increasingly critical of UK economic policy and the Bank of England’s monetary policy in particular. Is the Bank of England really losing grip of monetary policy? or are they doing the best job in difficult circumstances?

Criticism of the Bank of England Monetary Policy

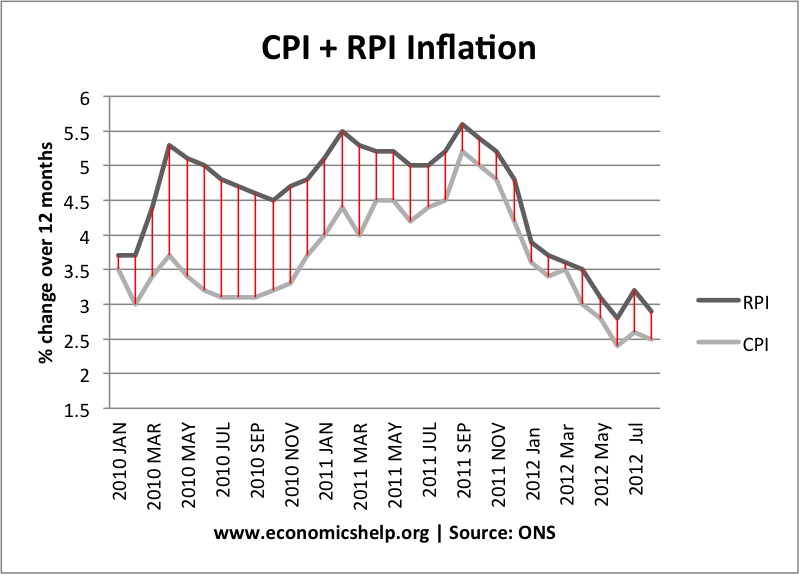

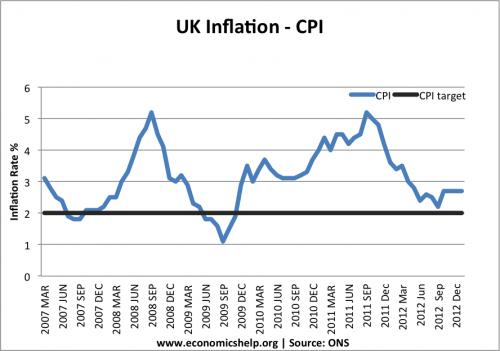

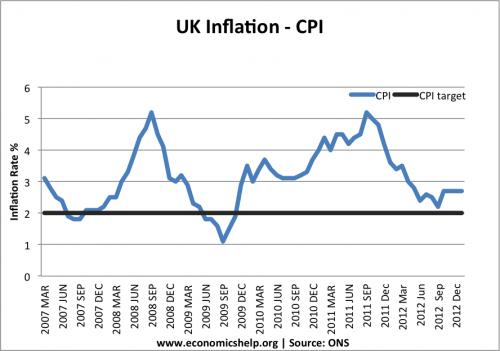

1. Inflation above target

The Bank of England have been given an inflation target of CPI 2% +/-1. Yet in the past five years, inflation has rarely been below the target. Inflation has frequently been higher than forecasts, and the Bank seem willing to tolerate a higher rate of inflation. In a recent article, David Smith writes:

“It (the B of E) has rarely hit the 2% inflation target in the past eight years and, on its own forecasts will not do so in the next 2-3 years. A decade of above-target inflation is, for any central bank, flaky. The Bank has lost its compass.” (the Bank of England has lost its compass)

The Economist also worries about the persistence of missing the inflation target.

“This time, however, the Bank thinks inflation will be above target throughout the two-year forecast period. That will equate to more than five years of missed targets or, as the Bank euphemistically puts it, a temporary, albeit protracted, period of above-target inflation. (Dear Joanna, be flexible)

2. Depreciation in Sterling

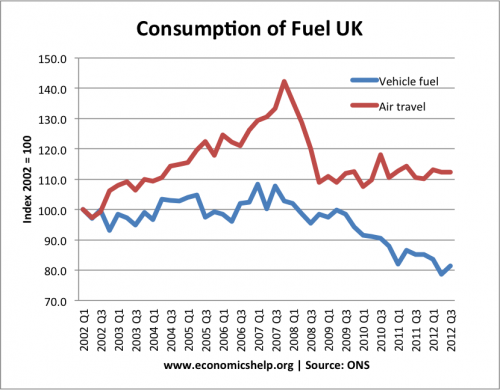

Despite the threat of above target inflation, the Bank has been quite sanguine about letting the Pound depreciate. The Bank of England have given the impression that a depreciation is necessary to restore the balance of the economy – improve the current account and increase exports. But, as noted, the depreciation in the Pound has given disappointing returns. For the depreciation, we risk more inflation and a decline in living standards.

3. Quantitative easing.

As a percentage of GDP, the UK has one of the largest programs of quantitative easing in the world. However, the Bank has no clear exit strategy, and some fear that we risk a bond bubble (rising bond yields), when we reverse the policy; it could leave the UK struggling to sell sufficient gilts to finance the large budget deficits.

In Defence of the Bank of England

1. Inflation in not the major problem

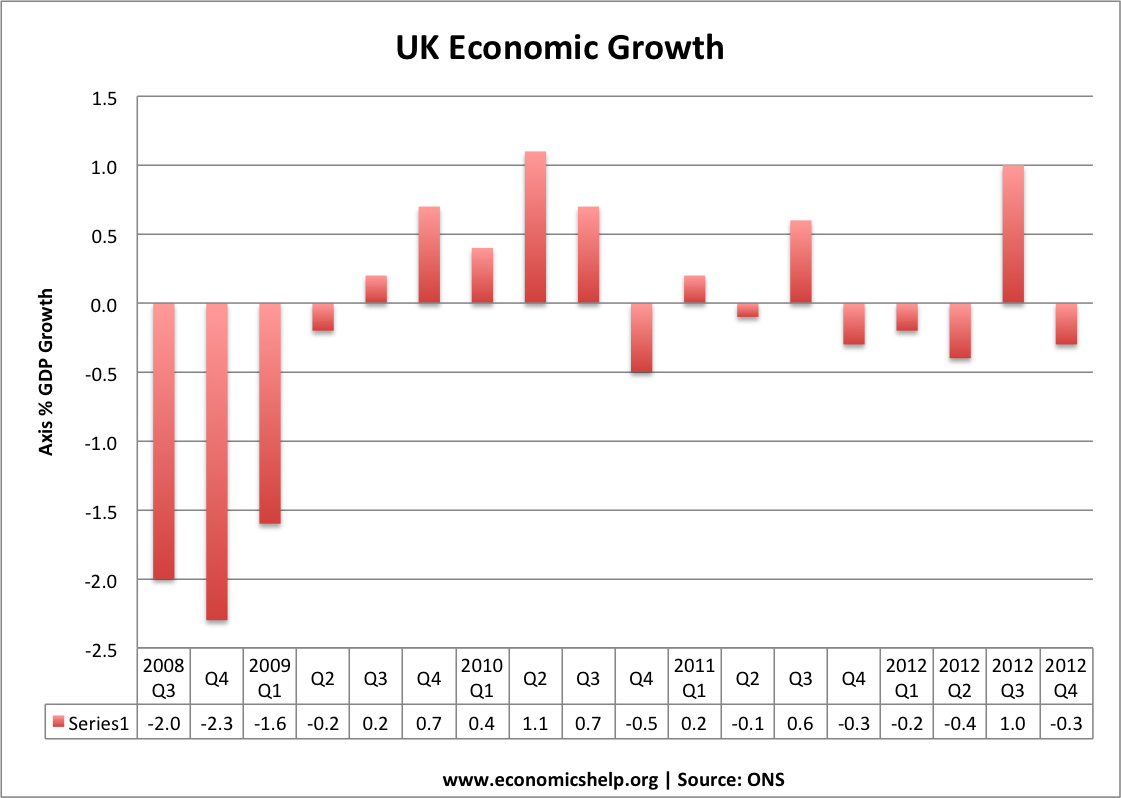

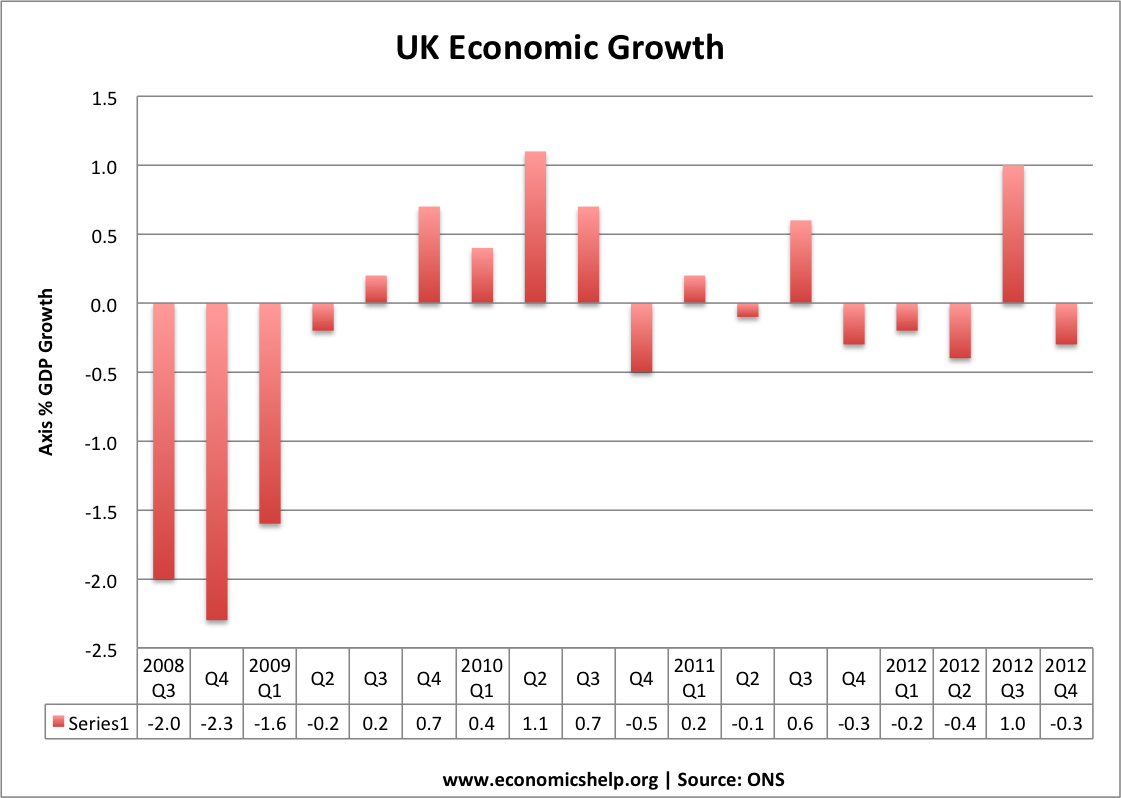

The UK has experienced a longer and deeper decline in GDP than the great depression. The UK looks to be heading to a triple dip recession. This shows that the economy is experiencing an unprecedented situation of depressed demand. Given fiscal tightening, weak global growth and very weak bank lending, the Bank of England should be pursuing monetary easing. To worry about inflation being slightly above target, during this prolonged recession would be to ignore the Bank’s dual mandate of inflation and economic growth. Even if they didn’t have a dual mandate, common sense suggests the monetary authorities should try to stimulate demand when you are experiencing a stagnating economy.

2. The inflation target is symmetrical – 1-3% not less than 2%

Some commentators have criticised the Bank for not keeping inflation below a target of 2%, but this ignores the fact the Bank of England have a target of 2% +/-1. Even by the strict criteria of inflation targeting, the Bank are targeting an inflation rate of 1-3%. It is true the ECB have an inflation target of less than 2%, but the performance of the EU economy doesn’t justify the UK suddenly adopting a stricter approach to inflation.

Read more