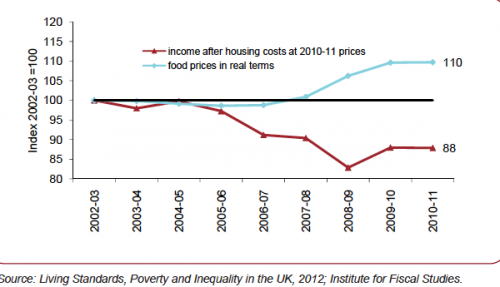

The past few years have seen a rapid rise in real food prices – especially, fruit, vegetables and meat. At the same time, we have seen falling real incomes for low-income decile groups. The consequence is that those on low incomes have been changing their diet in response to higher prices. With squeezed real incomes, there has been a greater preference for ‘cheap calories’ and lower demand for ‘more expensive calories’ – such as fruit and vegetables. Some fear the poorest are struggling to buy sufficient food.

The consequence of a switch to ‘cheap calories’ (e.g. saturated fats, processed sugar, less fruit and veg) has been to contribute to concerns about the nation’s health. During this period, obesity has continued to increase.

Price is not the only factor to influence the demand for food. But, increasingly, consumers are mentioning food prices and promotions as key factors in determining choice.

Income Decline for low-income groups

Median income after housing costs fell 12% between 2002-03 and 2010-11 for low-income decile households – while rising in all other income groups.

Food prices have risen 12% in real terms over the last five years taking us back to 1997 in terms of cost of food relative to other goods.