The UK national debt is the total amount of money the British government owes to the private sector and other purchasers of UK gilts (e.g. Bank of England).

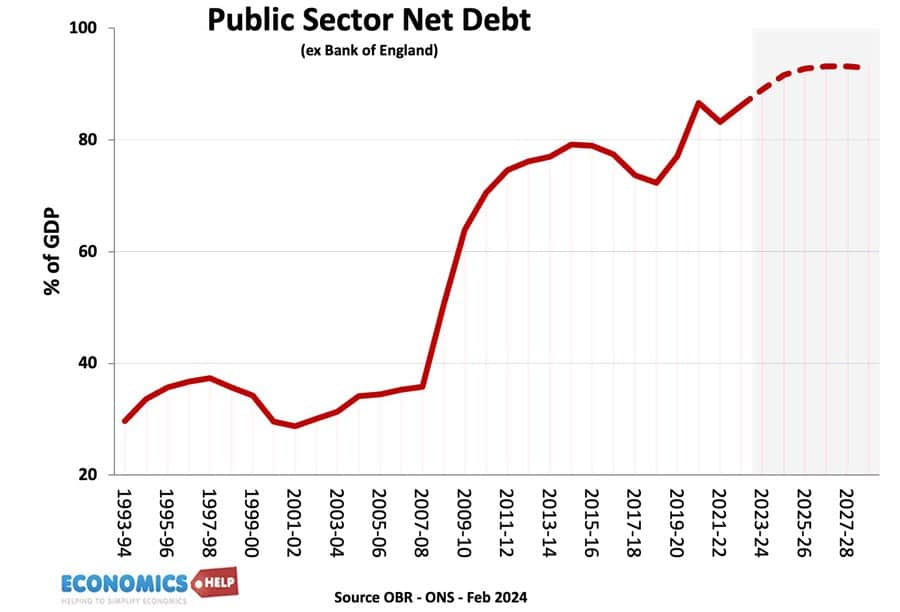

- In Jan 2024, UK public sector net debt was £2,685.6 billion or 97.7% of GDP

- This is the highest level of public sector debt since 1961.

- The OBR have forecast substantial rises in UK debt over the coming decade because of demographic factors, putting strain on UK spending.

- Source: [1. ONS public sector finances,- HF6X] (page updated 13 Feb 2024)

Source: ONS debt as % of GDP – HF6X | PUSF – public sector finances at ONS

Reasons for National debt

- Enables the government to spend more during periods of national crisis, e.g wars, pandemics, and recessions.

- In a recession, the government will automatically receive lower tax revenues (less VAT and income tax) and will have to spend more on benefits (e.g. more unemployment benefits) This causes a cyclical rise in debt.

- Extra government borrowing during a recession can help provide fiscal stimulus to promote economic recovery. By borrowing and then spending more, the government is injecting demand into the economy and this can help to reduce unemployment. This is known as fiscal policy and was advocated by J.M. Keynes.

- Strong market demand for government debt. Private investors buy gilts because they are seen as risk-free investments and there is also an annual dividend from the bond yield. Since 2009, there has been strong demand despite very low-interest rates, meaning the government can borrow very cheaply.

- Finance investment. The government could borrow to finance public investment projects that can lead to higher growth in the future.

- Political convenience. There is usually political pressure to cut taxes and increase government spending. Allowing debt to rise can be a way for the government to avoid difficult choices.

Forecast for the National debt?

Source: Fiscal risks and sustainability – OBR

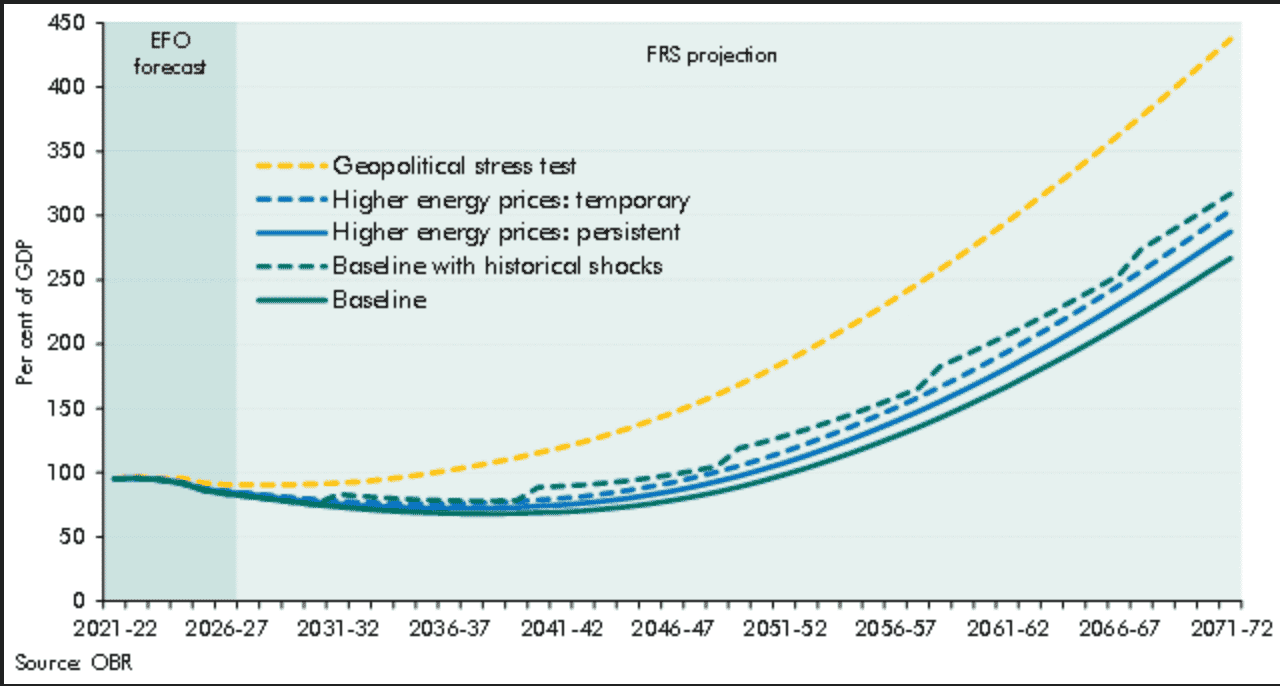

The OBR have forecast that, on our given trajectory, UK public sector debt could reach 350% of GDP within 50 years. The pessimistic outlook for national debt is made because

- An ageing population and demographic changes will put increased pressure on government spending, notably health care and pension spending.

- A smaller working population will limit UK’s productive capacity.

- Stress on finances from geopolitical events, such as frostier relations with China, Russia and the Middle East.

- Higher energy prices

- Costs of climate change.

- Declining tax revenues from petrol in a decarbonising economy.

- Low productivity growth of UK since the financial crash of 2009

- Recent boost to debt from the financial crisis and one-off cost of Coronovirus pandemic, which cut tax revenues and required government support for lockdown measures.

UK debt in context

Predicting debt for the next 50 years is difficult since we don’t know what kind of productivity improvements may come, e.g. continued gains in renewable energy may reduce the burden of higher oil and gas prices. Equally, the costs of environmental change could be worse.

History of the national debt

Main article: History of UK national debt

UK national debt since 1900

Source: Reinhart, Camen M. and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis,” NBER Working Paper 15795, March 2010. and OBR from 2010.

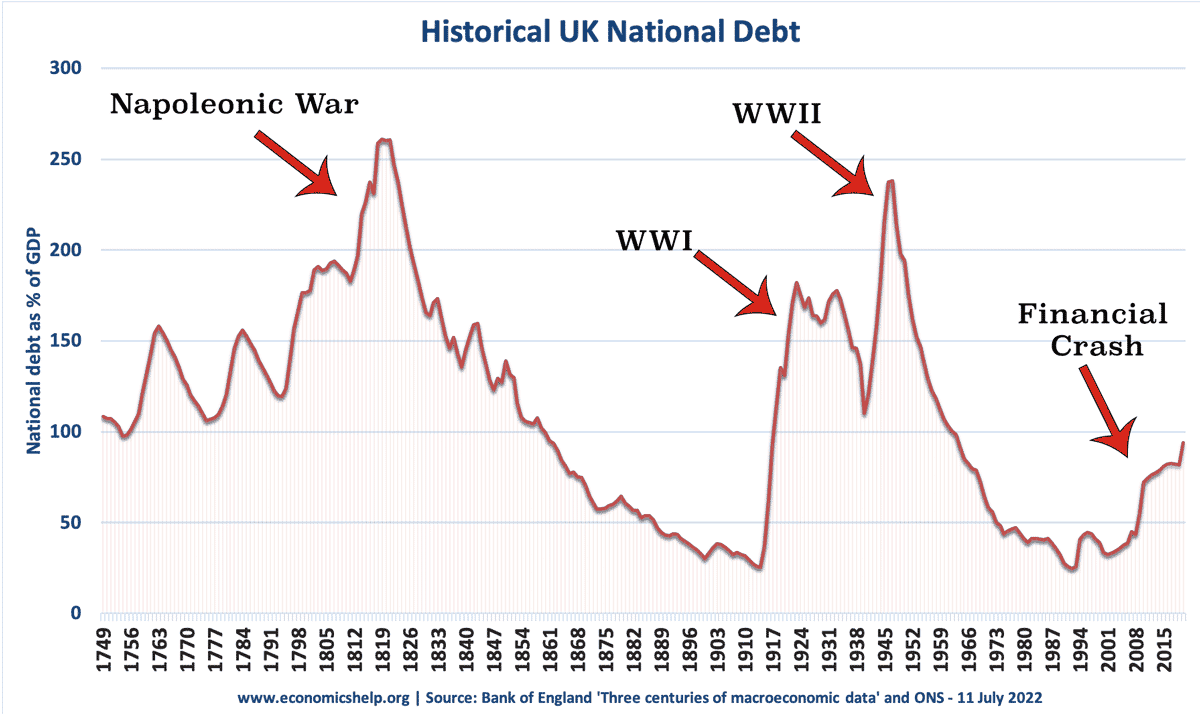

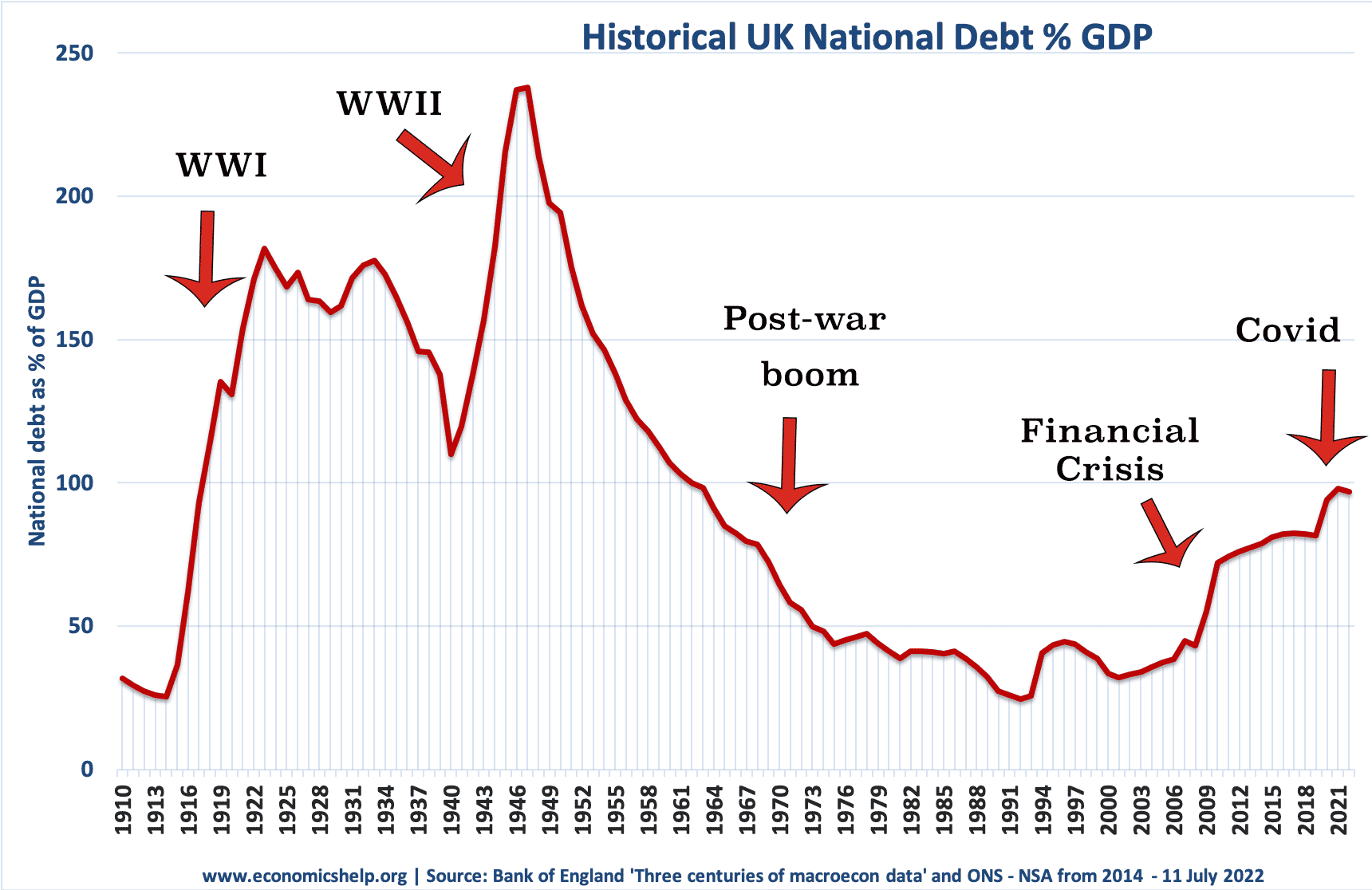

These graphs show that government debt as a % of GDP has been much higher in the past. Notably in the aftermath of the two world wars. This suggests that current UK debt is manageable compared to the early 1950s. (note, even with a national debt of 200% of GDP in the 1950s, UK avoided default and even managed to set up the welfare state and NHS.

Debt reduction and growth

The post-war levels of national debt suggest that high debt levels are not incompatible with rising living standards and high economic growth.

- The reduction in debt as a % of GDP 1950-1980 was primarily due to a prolonged period of economic growth. See: how the UK reduced debt in the post-war period

- This contrasts with the experience of the UK in the 1920s when in the post First World War, the UK adopted austerity policies (and high exchange rate) but failed to reduce debt to GDP. Debt in Post-First World War period.

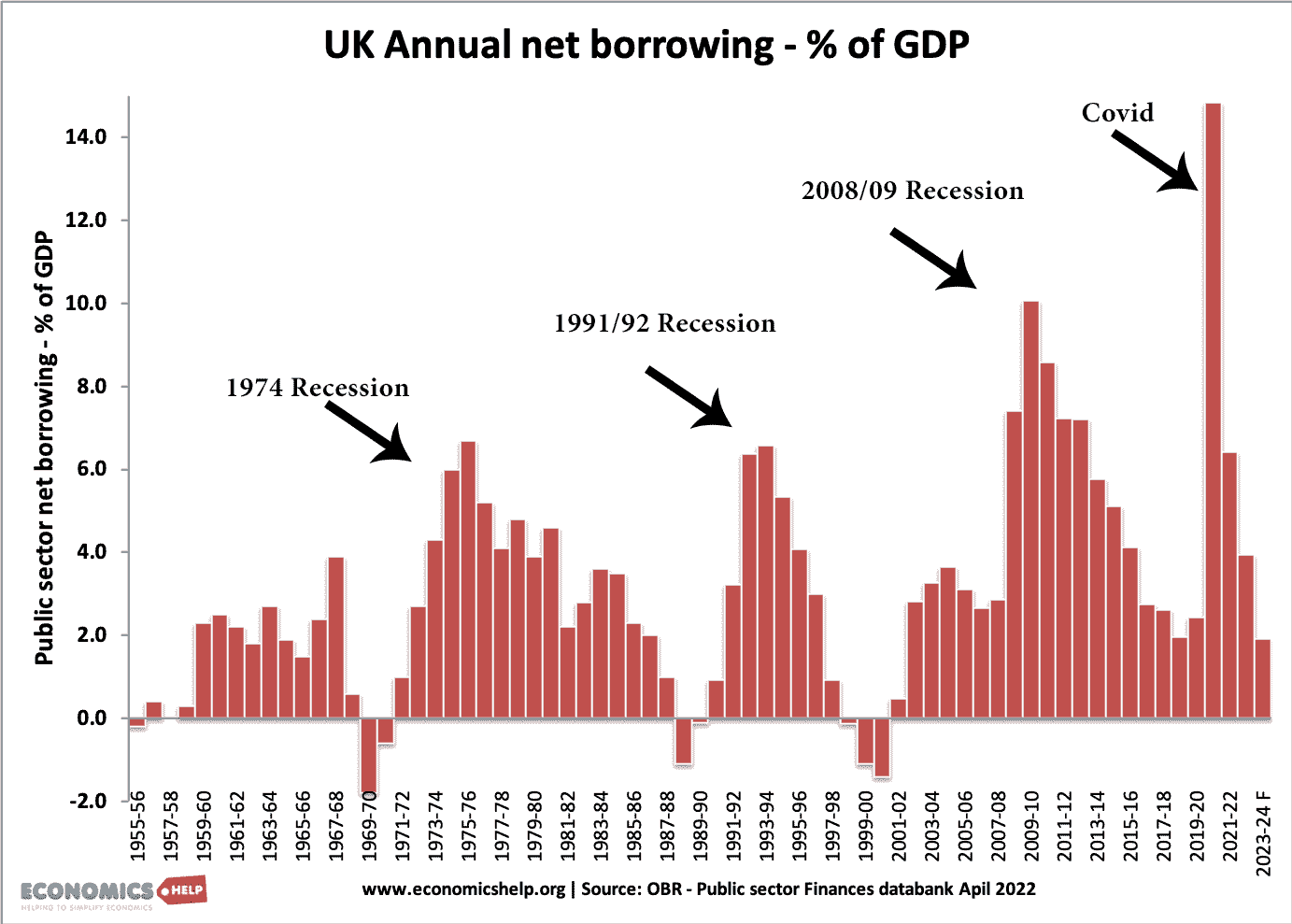

Budget deficit – annual borrowing

This is the amount the government has to borrow per year.

- In the financial year of 2021, PSNB ex was estimated to have been £146.8 billion.

Annual borrowing since 1950. Figures for 2023-24 are forecasts (and rather optimistic!)

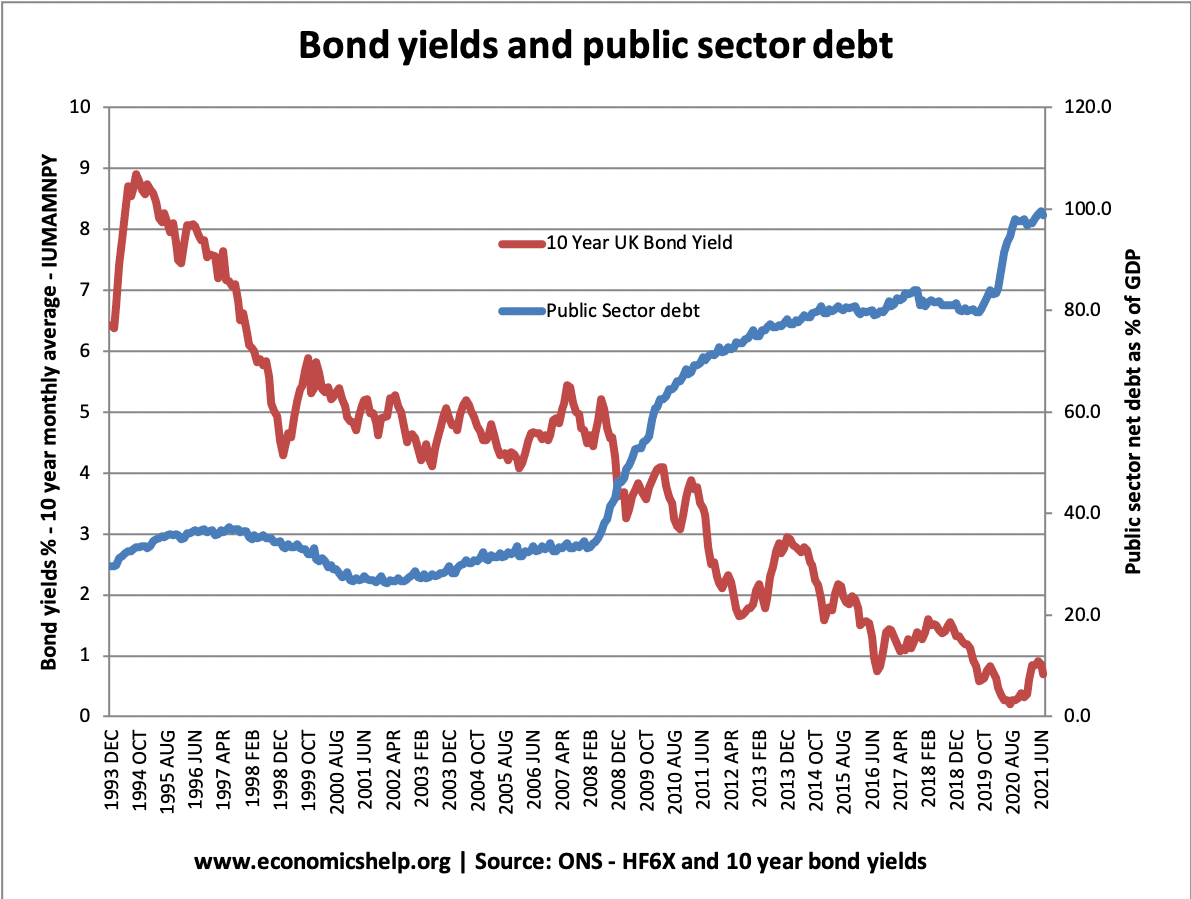

Debt and bond yields

Bond yields a the interest that the government pay bond/gilt holders. It reflects the cost of borrowing for the government. Lower bond yields reduce the cost of government borrowing.

Since 2007, UK bond yields have fallen. Countries in the Eurozone with similar debt levels saw a sharp rise in bond yields putting greater pressure on their government to cut spending quickly. However, being outside the Euro with an independent Central Bank (willing to act as lender of last resort to the government) means markets don’t fear a liquidity crisis in the UK; Euro members who don’t have a Central Bank willing to buy bonds during a liquidity crisis have been more at risk to rising bond yields and fears over government debt.

See also: Bond yields on European debt | (reasons for falling UK bond yields)

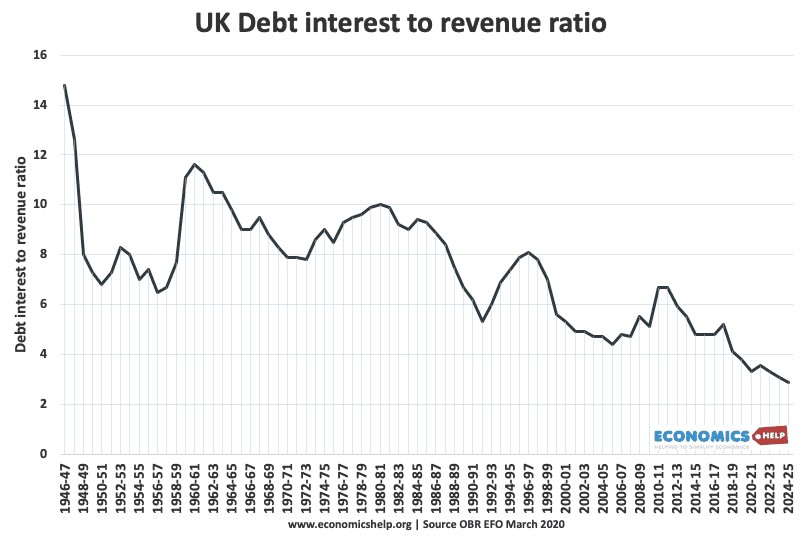

Cost of Interest Payments on National Debt

The cost of National debt is the interest the government has to pay on the bonds and gilts it sells. According to the OBR in 2022-23, debt interest payments will be £83 billion. (2.5% of GDP) or 5.2% of total spending. It is lower than in previous decades because of lower bond yields.

See also: UK Debt interest payments

The era of low interest rates post 1992 has helped to reduce UK debt interest payments as a ratio of government revenue. However, with interest rates and borrowing set to soar (2022/23, these predications will need to be revised upwards considerably.

Potential problems of National Debt

- Interest payments. The cost of paying interest on the government’s debt is very high. In 2011 debt interest payments will be £48 billion a year (est 3% of GDP). Public sector debt interest payments will be the 4th highest department after social security, health and education. Debt interest payments could rise close to £70bn given the forecast rise in national debt.

- Higher taxes / lower spending in the future.

- Crowding out of private sector investment/spending.

- The structural deficit will only get worse as an ageing population places greater strain on the UK’s pension liabilities. (demographic time bomb)

- Potential negative impact on the exchange rate (link)

- Potential of rising interest rates as markets become more reluctant to lend to the UK government.

However, government borrowing is not always as bad as people fear.

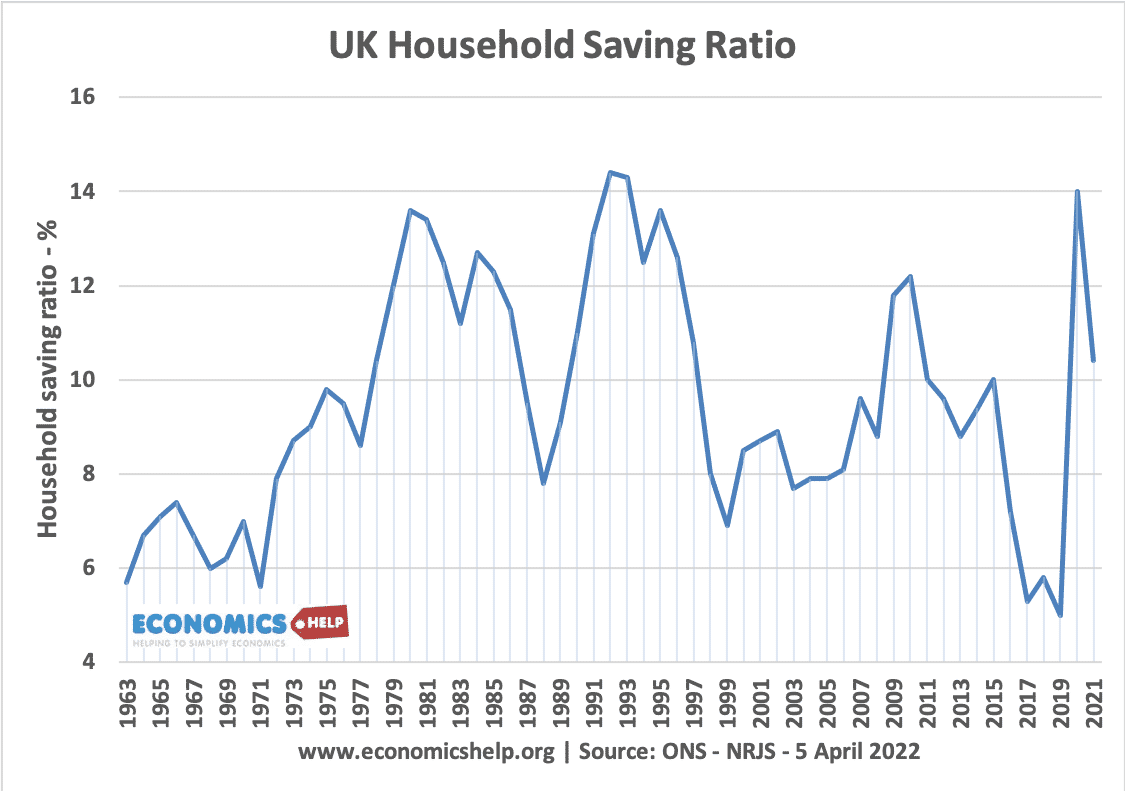

- Borrowing in a recession helps to offset a rise in private sector saving. Government borrowing helps maintain aggregate demand and prevents a fall in spending.

- In a liquidity trap and zero interest rates, governments can often borrow at very low rates for a long time (e.g. Japan and the UK) This is because people want to save and buy government bonds.

- Austerity measures (e.g. cutting spending and raising taxes) can lead to a decrease in economic growth and cause the deficit to remain the same % of GDP. Austerity measures and the economy | Timing of austerity

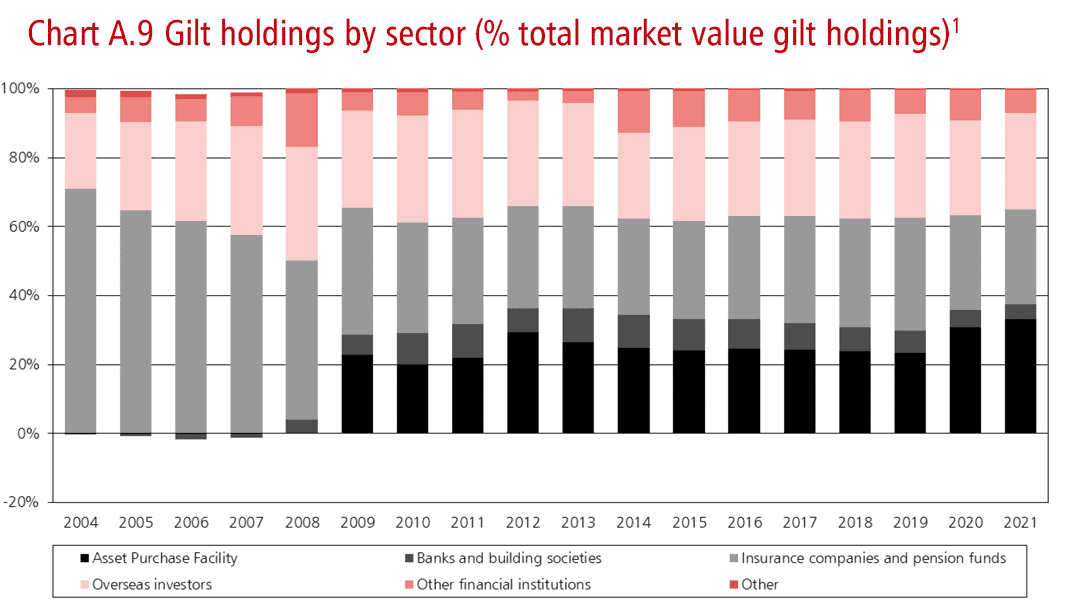

Who owns UK Debt?

The majority of UK debt used to be held by the UK private sector, in particular, UK insurance and pension funds. In recent years, the Bank of England has bought gilts taking its holding to 25% of UK public sector debt.

Source: DMO Debt Management Report 2022/23

- Overseas investors own about 28% of UK gilts (2022).

- The Asset Purchase Facility is purchases by the Bank of England as part of quantitive easing. This accounts for 26% of gilt holdings.

Total UK Debt – government + private

- Another way to examine UK debt is to look at both government debt and private debt combined.

- Total UK debt includes household sector debt, business sector debt, financial sector debt and government debt. This is over 500% of GDP. Total UK Debt

Private sector savings

When considering government borrowing, it is important to place it in context. From 2007 to 2012, we have seen a sharp rise in private sector saving (UK savings ratio). The private sector has been seeking to reduce their debt levels and increase savings (e.g. buying government bonds). This increase in savings led to a sharp fall in private sector spending and investment. The increase in government borrowing is making use of this steep increase in private sector savings and helping to offset the fall in AD. see: Private and public sector borrowing

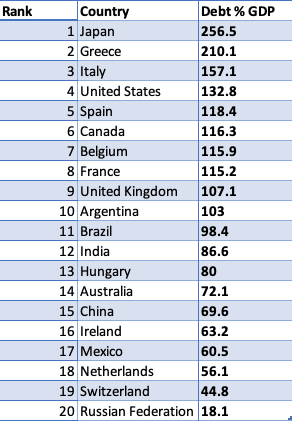

Comparison with other countries

Although 107% of GDP is high by recent UK standards, it is worth bearing in mind that other countries have a much bigger problem. Japan, for example, has a National debt of 256%, Italy is over 157%. The US national debt is over 132% of GDP. [See other countries debt].

How to reduce the debt to GDP ratio?

- Economic expansion which improves tax revenues and reduces spending on benefits like Job Seekers Allowance. The economic slowdown which has occurred since 2010 has pushed the UK into a period of slow economic growth – especially if we consider GDP per capita growth. Therefore the further squeeze on tax revenues has led to deficit-reduction targets being missed.

- Government spending cuts and tax increases (e.g. VAT) which improve public finances and deal with the structural deficit. The difficulty is the extent to which these spending cuts could reduce economic growth and hamper attempts to improve tax revenues. Some economists feel the timing of deficit consolidation is very important, and growth should come before fiscal consolidation.

- See: practical solutions to reducing debt without harming growth

Other countries debt

See also:

The U.K. is in big trouble, much more than in 1945, 1918, 1815 and 1713, when a lot of soldiers came home and became economically productive again. Debt was financed in the old days by Washington and earlier Amsterdam, but they will be unable to finance the U.K. government debt in the future. From 2006 to 2016 the Bank of England bought a third of all the U.K. government debt. It is now financed by the money in circulation, by people with banknotes in the bank and their pockets. The Bank of England has a weak position since 2006.

The U.K. and the other countries with FPTP voting system (U.S. Canada, France Italy and perhaps Australia) could go bankrupt in the next generation and stop paying intrest, which would mean the end of the welfare state. The figures for 2017 are still unknown, but the government debt percentage in countries like Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Netherlands, which have proportional representation, could go down with 3 to 5 percent, while it could go up or remain as it is this economically good year in countries with FPTP voting system, just as it did in previous years. For the U.K. the future is exceptionally bleak because of its very low savings rate, down to 11% in 2016 according to the World Bank.

Then there is Japan. It has the lowest intrest rates in the world, lower than tax haven Switzerland. Its debt is financed by its own savers. This 250% debt could mean frictions in the future, but by that time the U.K. is long finished.

What do you mean by financed by Washington and Amsterdam? Do you mean that they actually lost money on the loans?

Why we need more government debt in the UK

It’s a popular myth that government debt is a bad thing.

It’s a fact that the UK government does not need to issue debt. In the modern era of money the Bank of England can create any amount of money that the government requires without having to borrow or tax a penny of the sum in question. That is because all money is now, as a matter of fact, created out of thin air when banks lend money, including when the Bank of England lends directly to the Treasury. This is because all money is debt: if in doubt read what it says on a UK bank note, and realise that these are just debt, a fact that is confirmed by this cash being included in the national debt in the UK’s government accounts. Quantitative easing also proved this: £435 billion of UK national debt has been monetised since 2009. There is then no technical reason why all government debt could not be cancelled (as this QE debt has, in effect, been) in this way. As a result it has to be appreciated that when the UK has its own currency and its own central bank government debt is a choice and not something that has to be issued.

Another obvious fact: government debt is just another form of government created money. It’s convertible into cash, as QE proves. And all it provides is a savings mechanism. But it is a very important savings mechanism. In fact it’s the most secure for of saving available in the UK. That is because whatever happens the UK government will always be able to repay its debts because it can always, on demand, electronically create the cash to do so. It has that right. No one else has it in the same way. And creating that money is effectively costless: it happens simply by entering data into a computer.

Having made these obviously correct points (which appear to have passed most people by) let me now say why we need steady growth in government debt.

First, if we are to have some inflation (and we generally agree two to three per cent is good) then we need more money. And government debt is money. It is, in effect, the promise to pay that underpins the economy. So inflation says we need more of that debt each year. If we don’t get it then the economy is starved of cash and that causes economic stress, at the very least. It might also lead to more private debt, and that is much more dangerous as it carries much higher interest costs than government debt and so constrains real growth. So inflation demands more government debt. It’s the best deal for a growing economy that there is. That’s why governments have to create it.

Pensioners also demand more of that debt. The annuities that underpin all private pension payouts involve a delicate juggling act that balances life expectancy against the funds available and the return that they can generate. One variable where the risk can be reduced is the rate of return and the certainty that it will be paid. The return on government debt may be very low (it’s effectively negative at present after inflation is allowed for) but it is guaranteed to be paid, and that is exactly what pensioners want. No one wants their pension to expire before they do. So, government debt is what pension annuities are very largely invested in. And as we face an increase in private pensioners as the baby boom generation retires the need for government debt to underpin their pensions is growing.

Third, banks need this debt. When most people put money in the bank they assume it is safe. That is because the government guarantees the deposits most individuals make in banks so that if the bank fails the depositor will get their money back. That is the only reason most of us trust a bank. But this does not apply to businesses depositing millions of pounds in their bank accounts overnight, as happens every night in the UK. Those businesses have no such guarantee. If the bank fails on them, as Lehman did in 2008, then they might well go down with it. So they don’t deposit the cash. They enter into contracts with banks. The banks sell them government bonds in the evening, which the depositor then own, and which cannot fail because the UK government (unlike banks) can’t fail, and which the bank agrees to buy back in the morning at a slightly higher price, with the increase representing the interest due. If there were no government bonds to fulfil this role then the banking market would grind to a halt.

Fourth, at times like the present when the real rate of interest (as adjusted for inflation) is negative those who own government debt subsidise the taxpayer. The more debt there is the more the taxpayer is subsidised.

Fifth, interest paid on government debt is a good thing. As already noted, it underpins private pensions for a start. And a lot of the most stable savings funds. I’m not saying this is a perfectly equitable redistribution of wealth, because it is not. But I am also saying it is not income lost to the economy. And because it’s taxable some is even recovered. But saying it’s terrible is akin to an argument against usury and is again akin to an argument that a government should not have a role in seeking to provide a secure, stable and safe banking, pensions and savings sector in the country. I would argue that is precisely one of the roles government should have.

So we need debt, and because of inflation, growth and growing numbers of pensioners we need more of it. How much more? Notional UK national debt is now about £1.8 trillion and after QE it is around £1.4 trillion. Assume inflation of between 2% and 3% and how much extra debt do we need a year? Anything between £30 billion and something in excess of £50 billion would seem to be the answer. It’s not a precise science: there will be swings and roundabouts.

But the point is that this new debt is vital: it has to happen or the economy is harmed. And this sum excludes debt issued for specific purposes, like an infrastructure fund. Issue less than this and the economy will be in trouble. That’s a simple fact and explains why obsession with a balanced budget is so dangerous.

The final fallacy is that one day the debt will have to be repaid. No it won’t. That’s because this debt is money. That makes it unlike all other debt which is denominated in money. They’re simply not the same thing. Debt denominated in money has to be repaid. Debt that is money is only repaid if we want to destroy money. And why would we want to do that? Is anyone seriously suggesting that we can live in a moneyless society in future? I seriously doubt it. And in that case national debt does not have to be repaid, ever, which is exactly what history tells us.

Government debt is a good thing. The danger is inherent in the myth that it isn’t.

Where on a UK bank note does it say its debt?

Where it says “I promise to bay the bearer”.

Pretty well put the only problem left is that most of the Debt / money lives in off-shore accounts and is needed to move around our society.

So are you saying the money which the uk government borrows is made out of thin air by the bank of England; and the bank sells the debt to private organisations and persons. So the tax payer pays interest for money made out of thin air, with no intrinsic value. Is this not robbery of wealth- £68 billion.

I find many of your “obvious facts” frankly ridiculous. You CANNOT just cancel £1.78 Trillion of government debt. Quantitative Easing is NOT a way of cancelling debt for free. That is NOT how sustained inflation works. You CANNOT just print money without serious consequences. A bank note is NOT money (in the pure sense of the term) so you CANNOT compare it to a BoE monetary injection, as the bank note is far futher down the ‘higherarchy of money’, so a significantly higher volume of it can exist than BoE reserves.

Quantitative Easing is an open market opperation, in which the Central Bank buys up government bonds using printed money. The purpose of it is to increase money circulation in the economy in order to stimulate aggregate demand. If you simply use it to pay off government debt, everytime government debt gets out of hand, inflation would go through the roof. Inflation in the UK is currently around 2.1%. If you injected an extra £1.78 trillion into the money supply (almost double the amount injected in QE1, QE2 and QE3 combined) inflation would increase rapidly, this would lead to the velocity of money increasing, as it loses its value at an alarming rate, this would increase demand pull inflation. This would spiral into a hyperinflationary crisis, absolutely destroying the UK economy (same effect as Weimar Germany).

I won’t even waste my energy on explaining why the UK could not just default.

Most of what you have claimed is not applicable to the levels we are talking about. Debt expansion is necessary, monetary expansion is necessary, but not in anything approaching the volume that you are talking about.

Just PLEASE do a MOOC or something on monetary economics.

Also before you tell me that they are not printing money, it is digital. Printed money is just the term used for monetary injection.

Tell Argentina that government debt isn’t a bad thing. The nonsense here is evident by the comment “we generally agree two to three per cent is good”. Who agrees…..pensioners or a fixed income? In a credit drive economy the inflation and the fractional banking system are essential to keeping it all afloat. The problem is the real income produced per unit of debt has collapsed. The baby boomers are retiring and getting set to liquidate their assets… hoping for high prices. Few in the UK save much money and everyone wants more spent on education and national health. The country is simply no longer a power house of ideas and capital it once was. I can’t predict with some certainty that government debt will soar during the next recession, yet interest rates are close to century lows. Pension funds can barely make money and underfunding is rampant. WHEN interest rates rise again by even a couple of percent bankruptcies will soar. Then all you have to do is look at politicians today…. Government debt will head higher soon….

Agreed debt is necessary within the balancing act of monetary policy. If done correctly it equates to faith in a countries/banks accounting or a lack of faith in its in ability to account. The determination of this balancing act is never certain and is determined by the market place at all levels and the results are not always clear and mistakes can be made. If it was an exact science we would all be rich an no one would be poor. We can only determine for ourselves as we climb or fall the pyramid.

Nice one Richard. Most people don’t understand how our money system works. You’ve hit the spot.

BOE balance sheet expansion or contraction is basically how we tune the money supply to support the economy and keep inflation in a healthy range.

I think that it is unfortunate that we call balance sheet expansion debt, it misleads the majority, who think that the nation Is in some horrendous debt situation. (Total Myth)

Anyone who thinks a debt problem can be dealt with by taking on even more debt is asking for trouble.

I have just watched ‘The Bank That Almost Broke Britain’ on iPlayer and I am still confused. How much of UK national debt is due to the bank bailout? Therefore, how much of the austerity was due to it? I am struggling to find a straightforward answer

Bank bailout was £500bn and has largely been repaid, although the public purse has taken a loss of £27Bn which is small beer when you look at the numbers. Most of this is increased borrowing as a result of recession/economic downturn, not austerity. Austerity was used as a means to try and reduce the ongoing deficit, so that we didn’t borrow more.

Can anyone explain why the UK’s National Debt is now nearly 96.7% of GDP compared to 86.6% of GDP this time last year? Source: World Debt Clock (figures shown in $$$). We appear to have borrowed an extra $1T since Christmas! http://www.usdebtclock.org/world-debt-clock.html

No, the national debt was 1.83 trillion in December and still rising.

Where you get that figure from published figures put it at 84.1% it actually fell for the first time since the 08 crisis.

So the last Government to reduce the national debt was Gordon Brown in Blair’s 1st Labour Government?

And austerity has failed.

The best fix for the ever-expanding debt problem would be a thriving economy, with everyone in jobs paid a wage that does not require Government subsidy and business profits properly taxed?

Anything wrong with that analysis?

“The best fix for the ever-expanding debt problem” is to follow the Macawber principle (currency updated)

– Have £1, spend £1.06 = result misery.

– Have £1, spend 94p = result happiness.

Apart from hsort term blips spending needs to be managed according to how much is coming in

It is also non-sensical to borrow and pay interest on money that is then given away.

Surely when we have near full employment as we have now the Government should be producing a surplus (as in the late 1990s) and reducing national debt. Not to do so means that we have a structural problem in the UK?

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/152882/economics/what-is-a-structural-deficit-problem/

One more question: if the BoE buys Government debt, where does it get the ‘money’ from to do this?

I assume it is Government that issues gilts not the BoE

At the time of the Economic collapse 2007/ 2008 or near the end of that period in 2010 the Labour admionistration had actually started to pull out of recession – True or False ?

Round about 2010 there was a theory put about by an American University that if your Debt to GDP ratio rose above the arbnitrarty figure of 90% then your economy was doomed forever and many governments and the ECB in particular used this thesis to introduce harsh Austerity measures. This University theory was later debunked – True or False ?

If one looked at the UK’s Historicalk Debt to GDP ratio; at the time austerity was introduced; the Debt to GDP ratio was last at this 2010 level in 1966. Having lived in 1966 there was no massive economc requirement to reduce public spending at that time ie everything was fine. So was this “need” to take drastic action just all rubbish ?

thanks Brett

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/153626/debt/was-austerity-necessary-in-2010/

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/153619/economics/when-did-the-recovery-from-the-2009-recession-occur/

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/7541/debt/does-government-debt-lead-to-lower-economic-growth/

Hi Everyone…

This discussion is the most important in the whole of our modern history. This is because the world is moving into a different era of work, capital and consumerism. The human race has never been down this path before, and it will change everything in the ‘near future’ ie within an economic time-scale of 20 to 50 years – which is within one working lifetime of an existing child.

The Point I shall TRY to make is… money and debt, as we currently understand it, will effectively CEASE TO EXIST. This is because the efficiency of production will tend towards 100% within the next 50 years…. please let me explain before you dismiss this as nonsense….

The whole concept of jobs/efficiency/debt is going to change EXPONENTIALLY. Companies employ people and own the means to production, competition increases efficiencies. This, for many people is the way capitalism should work, there are the owners of the capital and the workers. The money flows around, money base expands to meet the increase in efficiency (worker output per unit of capital), and all is well, (more or less).

However, a change… a massive change is coming. The workers who make the products and services will, within a time-scale of 20 to 50 years be replaced by ‘Smart Robots’…. and these will rise exponentially because they will manufacture themselves… 2, 4, 8, 16, 32…..then billions

This is a world transformation – no one will be able to hide from its reach – except the (few) very rich and very powerful. The Smart Robot will make the Smart Robot – this will lead to an exponential rise of robotic systems and Robotic ‘wealth creation’. In 50 years time very few people will have jobs as we know them today (people may choose to work, but that will be their choice). There will be plenty of wealth – but people will not be creating it. *We see this trend already… take UBA where their efficiency is massive…add in the driverless vehicle (there are already taxis without ANY driver in Arizona) and you have 98% efficiency.

Few people understand the capability of this new technology, and fewer see the transformation coming – think of the railroad and how it changed the world’s economies. Interestingly, it also became exponential as the railroad built the next bit of railroad… the Smart Robot will do exactly the same.

BUT – Who then owns these Robots? Who owns the ‘means to production’ and the many services? No one will answer this question, people say … but someone must own the capital … but WHY?

So, when we replace the ‘worker’… what happens to the standard economic theories? Does capital matter any more? If so, why when the Robots can make as much as the society needs without any help… do we need to consider who owns the capital? If just a ‘few’ own the capital, the rest of us are effectively enslaved ‘users’ without any say about a fair share out?

So, if the capital does not matter what happens to debt? Who cares what the debt is? Everyone can have whatever they want (subject to the planets resources), the questions will be about the SHARE OUT of the total world resources. Debt therefore will be meaningless, if you print more money, then it will go straight into inflation, as there is no middle man (work / capital / efficiency / output). If you borrow – what would you do with the money – you can’t use it to create any wealth as wealth production is 100% efficient already. If you spend you borrowed money, since the available resources are finite – this just inflates the prices of everything.

Work, Capital, Money & Debt become meaningless. To me this final outcome seems irresistible, all I am not sure about is the timescales… and can we create a sensible transition?

Your esteemed thoughts appreciated.

Thanks for reading.

CST

Oh for a one handed economist !

This is a somewhat tardy contribution. BUT – one problem with such diascussions is that they do tend to remain on the side of fincial/monetary/price equations.

Any discussion or use of increased debt in funding our present need for recovery surely must centre on the planned usage of debt. It increased if fore-planned and transparent in a political regime that has a real democratic mandate, then at the core must be an intention to use increased debt to fund a mixture of medium and long term real public projects that together could constitute a Keynesian style of positive intervention. Do not howl yet. Its true that Keynes himself would feel nauseus at this bare statement, if only because of the intricacies of his theory of money. BUT, whether increased debt can be considered a true burden when it is actually used to fund productive growth of industries and services under increasing levels of productivity (not measuring the latter primarily in labour productivity terms but at least attempting a bit of TFP calculation!) then what matters is sn astute period of national accounting.

Even old man Smith himself allowed for increased debt and did so in apologising for increased expenditure by the state in times of war (The Wealth of Nations 1776). we have suffered something that all media have labelled warlike buy without anything like the real asset and building destruction of material warfare at a world level. There is therefore a better chance of reinstating a policy of recovery by debt.

A major problem is that in most democratic capitalist nations debt proportions have been on the sporadic increase since 2008, certainly not just since the pandemic. In some of the very large and hitheto growing systems outside of Europe, Asia and the Anglophone nations debt has remained modest for several reasons – some do not have the status to borrow very freely or at low cost in either public or private sectors; in many important sectors growth really has been almost self-funding, not requiring debt; in all they have had lower covidity measured by cases per million, deaths per million and death/cases%, than the richer nations, for reasons that I have considered very extensively elsewhere, meaning that borrowing for short-term covidity was very small.

This backdrop means that electorates will be very wary indeed when any group of our present populist politicians begin to come out with borrowing/spending plans of this sort, even if they mange to be coherent in media delivery. They are often not. When the UK Labour Party in an earlier election fight against what were by then a group surrounding Boris Johnson and an increasingly rightest centre, the combination of a fairly incoherent Labour leadership under Jeremy Corbyn with a perfectly sensible and debatable economic plan from his major economic minister (John McDonald), never ever emerged as a power in the debate as it was seen as complex, non-populist, even threateneing more taxes, and requiring of too much in the way of best possible outcomes. The Tories cam in on a landslide and threaten to survive even the present gruesome turn of events.

So, the issue is far more one of political economy than of financial/public sector economics, for an appeal to realmproduction of real goods and services requires an older trust of democratic processes, the power of elections and or trusted regimes, it requires a public closeness of debate and policy formation that is both close in preparing the ground prior to public delivery and well-prepared for the subsequnet policy delivery process itself. This is where democracy is falling short of its old potential. It was alway built upon colonialism and exploitation, but it was also mostly forced to be transparent because large social classes were involved in political outcomes very directly through mass elections, local-government based active communities, and a media that could be held up to face the consequences of its own bias or ineptitude, at least more so than can be said at present.

And political economy is no technical matter, viewable through the equations of even the much modified neo-classical economics that we have inherited from the 1950s. It requires some dort of organic civil society. This sounds elitest and is dangerously back to the normative. I am sorry about that. But it can be seen with more sympathy. it is poossible through the political process to forward a 21st century New Deal in which major cpaitalist nations agree to a broad [pattern of interventionism in which the middle income nations ar3=e directly involved as private and public investors and traders. Growth in this latter group shall be far higher than that in the ‘mature industrial’ democratic capitalist nations for some time, assuming the absence of this Keynesian program. Assuming some greater collaboration the divergence would be lesser, the overall average performance would be greater, and there might be some movement for those nations who have considerably increased their levels of economic freedoms, to emerge as nations of greater cultural and political freedom. Old men and their narrow regimes need not last for too long, and a rising middle class is a wonderous thing.

Ok so we have moved an awful long way from the first comment on this long chain! But it might be worth revisiting those early comments, after all much has gone under the bridge since then and we are in greater rather than lesser trouble at a world level. I leave you with a terrible irony – in the long 1950s-1980s period when western economists and politicians were lecturing the 3rd world on what to do about their poverty and misery, when they werre very stringent with the then IMF regulations on who could lend what to wheom and who needed to up their exchange rates and so on, very little 3rd world development actually occured. The breakaway of the Newly Industrial Economies of East Asia was but a happy proportion, and the Chinese revovation was not even recognised by most analysts. Now the whole conception of a world of poverty has been massively interrupted, lower income nations are now under more influence, investment and trade from East Asian – especially China and Japan who were externally invisible in the 1970s – the third world really is shrinking, much more than in the earlier years of Cold War and rampant capitalism, the world is actually a lot better off. But still we are messing up.

“In August 2022, UK public sector net debt was £2,427.5 or around 96.6% of GDP).”

Only two and a half grand? :-/

Thanks for spotting. Small matter of missing billion. In August 2022, UK public sector net debt was £2,427.5 bn or around 96.6% of GDP

The most common measure of National Debt is as percentage of GDP. However, to put debt into perspective, (as a non-economist), I suggest we also examine other figures such as:

1. Ratio of debt over government income £2,347.7 billion divided by £820 billion = 2.863

2. Debt per capita of the working population of 32.8 million.

Debt £2,347,700 million divided by working population 32.8 million = £73,365!